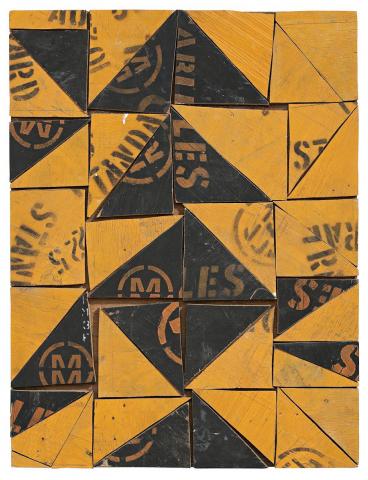

PAVEMENT II, 1997

ROSALIE GASCOIGNE

sawn wood on plywood

66.0 x 50.5 cm

signed, dated and inscribed verso: Rosalie Gascoigne / 1997 / PAVEMENT II

Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide

Private collection, Sydney

Gould Galleries, Melbourne

Private collection, Adelaide

Rosalie Gascoigne, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide, 19 August – 13 September 1998, cat. 13, (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Gouldmodern, Gould Galleries, Melbourne, 8 February – 10 March 2002, Gould Galleries, Sydney, 16 March – 14 April 2002, cat. 30, (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Pavement, 1998, sawn wood on plywood, 69.0 × 52.0 cm, exhibited Rosalie Gascoigne, 1998, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

'Gascoigne's use of modernist strategies, her simple but complex means of construction - those of fragmentation, re-assemblage, repetition, tessellation and compression - effect an ordering and accentuation which is also poetic in its workings. In all this, Gascoigne's processes of handcrafting are foregrounded, and communicated through an exceptional economy of means. She experiences, selects and creates, using a relatively narrow range of materials in order to present the work to us resonating with a virtually endless allusive power. Her results are spectacular, exquisite distillations and extractions, grounded in her personalised experience of the land.'1

With her training in the formal discipline of Ikebana complementing her intuitive understanding of the nature of materials, her deep attachment to her environment and later interest in modern art, Rosalie Gascoigne is regarded as one of Australia's most revered assemblage artists.

Juxtaposing triangles sawn from wooden industrial cable spools, Pavement II, 1997 is an impressive example of the artist's signature black-on-gold assemblages which first brought Gascoigne widespread acclaim almost a decade earlier with works such as the monumental Monaro, 1989 (Art Gallery of Western Australia). Occupying that space between 'the world, and the world of art',2 these compositions are artful and refined, yet always bear strong affinities with her immediate surroundings, powerfully evoking remembered feelings or memories in relationship to the landscape; '...they are instances of emotion recollected in tranquility' to quote a phrase of Wordsworth's which was so dear to her. In the same vein as the Romantic poets which she so admired, Gascoigne thus aspires to an art that is both 'illusive and allusive'. Here the geometric arrangement with its emphatic frontality, repetition and interest in the formal qualities of colour, texture and movement is unmistakably aligned with high Modernist practice; simultaneously however, the abstraction eloquently echoes tessellated floors familiar to us all (and perhaps originally inspired by the artist's own experience of the celebrated marble pavements of Piazza San Marco, Venice which she had no doubt visited while representing Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1982).

With their rhythmic pattern composed of letters, such compositions have not surprisingly been described as 'concrete stammering poems'3 a perceptive analogy, especially given the artist's predilection for poetry from Shakespeare to Plath. Notwithstanding, Gascoigne stresses that the flickering word fragments, though carefully arranged, are not intended to be read literally: 'Placement of letters is important, but it's not a matter of reading the text - it's a matter of getting a visually pleasing result.'4 Similarly, her titles are not literal but rather, 'leave room for the viewer', imbued with multiple levels of meaning to be deciphered. Indeed, as Gascoigne reiterates, ultimately her work is about 'the pleasures of the eye', with her formal manipulations of natural and semi-industrial debris to be appreciated simply as objects of aesthetic delight. Like the materials themselves, beauty is a quality that is easily and thoughtlessly discarded; as John McDonald muses, 'When we value things for their perceived usefulness, we overlook a more fundamental necessity. Life is impoverished by the inability to recognise beauty in even the most humble guise.'5

1. Edwards, D., Rosalie Gascoigne: Materials as Landscape, Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1998, p. 11

2. Ibid., p. 15

3. MacDonald, V., Rosalie Gascoigne, Regaro, Sydney, 1998, p. 34

4. Ibid., p. 35

5. McDonald, J., 'Introduction', MacDonald, V., ibid., p. 7

VERONICA ANGELATOS