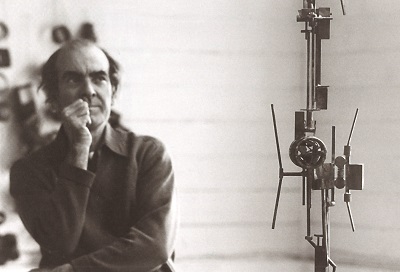

ROBERT KLIPPEL, 1960s – 1970s

Robert Klippel’s grasp of the aesthetic potential of everyday objects changed forever on 1 April 1948 during a train trip in England. Perhaps it was the relaxing effects of train travel or simply a mesmeric response to the flickering screen of images that flashed through a carriage window. He was returning to London from Cornwall and during the 400 kilometres journey he noted:

the variety of “constructional” elements which are before our eyes … signals, towers, telegraph poles, chimneys, cranes, masts, radar equipment, street lamp-posts, step ladders, water tanks, windmills, dredges, church spires, lighthouses, ventilators, etc., etc., all vertical, man-made – a relationship existing with the organic trees and men … I can’t see why an artist can’t use such exciting elements in his work – but no! – practically everybody says that the figure is the only thing for sculpture. It is incredible! (author’s italics)1

This penetrating “all-at-once” observation had its backstory. Klippel had been privately musing along these lines for more than two years. His many personal notes and items of documentary evidence indicate that his “on the train” insight formed its roots during the mid-Forties in Sydney, found its realization during the late-Forties in London and flowered in Paris.

While in Paris from 1949 to 1950, Klippel became a close friend of the French-Canadian artist Jean-Paul Riopelle and grew more fully aware of the use of the Principle of Chance – an art concept that essentially rested upon mental associationalism. Certainly, chance has been used for divination for aeons, but the European Modernists’ special use of it aimed to uncover the Unconscious, reveal unpremeditated images, prompt new juxtapositions and free the creative mind. Klippel studiously avoided any psychological aims (for him there was no inner ‘voice’ or mental mirror) and was more interested in considering chance to be a universal force that was almost spiritual in its operative dimensions, especially after he heard the engrossing lectures of the Indian mystic Krishnamurti in Paris in mid-1950.

Subsequently, Klippel experimented with the use of chance and welcomed it as a depersonalizing device that freed the creative mind – chance events, chance encounters, chance finds, found objects – all now pointed to an artistic use and an indeterminable aesthetic potential. His sculptural compositions, welded, brazed, soldered or glued, slowly started to use scattered images, common items and constructional fragments simply for their visually jarring and dynamic artistic effects.

This was especially the case in late-1950 when he returned to Sydney. His artwork there started to incorporate flat sheets of wood, metal and plastic combined with connecting wires and supporting steel rods, often in tripods, in geometric compositions that fell in line with the bold intersecting forms of School of Paris abstraction in the Fifties. At times, these new constructional sculptures seem to echo Desargues’ theorem of projective geometry, but mostly their sail-like triangular shapes radiate a sense of the operation of underlying universal patterns. At other times, it is as though Klippel was using found mechanical items as component parts of the ‘visual grammar’ of new three-dimensional sentences. Like literature, sculpture had to shape and give shape to thought. It is this that gives Klippel’s sculptures their sense of structured connectedness.

Klippel always felt that he was tapping at the window of a felt but unseen omnipresent order. But, of course, unseen things have no perceptible form so Klippel’s structures were created to act as emblematic stand-ins for palpable harmonies. Considered in this way, Parisian automatism found its apotheosis with Klippel in faraway Sydney – its original aim of searching for the harmonised ordered centre in the self was transmuted by the artist’s search for the harmonised ordered centre in everything – wherever he found it. It is this that gives Klippel’s sculptures their “just-so” sense of being.

Furthermore, it is significant Klippel thought of Modern sculpture as the culmination of a carefully considered arrangement of abstract, rather than figurative or naturalistic, entities. Certainly, his earliest notebooks carry some drawings of the human figure, but these are usually divided, segmented or sectioned with grid lines marking up compartmentalized parts of the whole. Discounting some early biomorphic sculptures made in 1944 and 1945, Klippel’s sculptural wholes after 1946, especially those of the Sixties and Seventies, are invariably envisioned as sums of parts, as unified components or as combined relationships of abstracted compositional elements – in our times; to our eyes, this alone already propels his works beyond the world of statuary into the world of sculpture.

In essence, Klippel’s magisterial sculptural constructions and bronzes of the Sixties and Seventies are reliant upon gestaltism – the visual impact of an organised whole that is perceived as being more than the sum of its parts. All those carefully arbitrated outward forms seem to thrust, dance, swirl, pose and project and as they do they mirror not the life of Nature (Klippel never imitated the natural), but the inner life of their creator as he orchestrated them into sculptural existence.

One of the essential attributes of Klippel as an artist was his Zen-like focussed detachment; his works show no hints of personal trauma, no anguished elements, no fulmination or anger, no expressionistic outpourings, no socio-political ‘issues’ and no hint of the cult of personality. Rather, they stand as though they were self-made entities that show aesthetic exactitude, harmonised order, tonal orchestration, nuanced spatial analysis, finessed placement, acute formal sensibility and, above all, they somehow possess a formal modesty – they do not “shout”. All of his artworks – sculptures, assemblages, bronzes, drawings, collages, watercolours, paintings – bear witness to an uncommonly dedicated and outwardly simple existence that engendered and sheltered the most subtly refined inner life.

1. Klippel, R., 1 April 1948, cited in Gleeson, J., Robert Klippel, Bay Books, Sydney, 1983, p. 45

KEN WACH

Associate Professor Ken Wach wrote the catalogue for the exhibition Robert Klippel: The American and European Years at Galerie Gmurzynska in Zürich in June 2013 – the first Klippel exhibition in Europe for sixty-three years. He was invited to give an address at the exhibition opening at the Baur au Lac Hotel. Robert Klippel is internationally represented by Galerie Gmurzynska in Zürich.