(1899 - 1970)

William Dobell

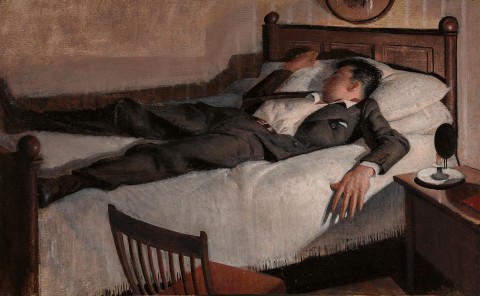

Young man sleeping, c.1936

oil on board

Estate of the artist, New South Wales

Thence by descent

Private collection, the artist’s nephew

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 22 August 1994, lot 76

Private collection, Melbourne

William Dobell: The Painter's Progress, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 14 February – 27 April 1997, Newcastle Region Art Gallery, Newcastle, 7 May – 6 July 1997, Museum of Modern Art at Heide, Melbourne, 29 July – 21 September 1997, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 25 October – 7 December 1997, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, 8 January – 1 March 1998 (label attached verso)

Pearce, B., William Dobell: The Painter's Progress, The Beagle Press, Sydney, 1997, cat. 11b, pp. 34, 49 (illus.)

Study for Young Man Sleeping, c.1936, pencil on paper, 26.0 x 35.7 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

In 1929, William Dobell was awarded the Society of Artists’ two-year travelling scholarship following an extended period of study at Julian’s Ashton’s art school in Sydney. The award came with a stipend of £250 per year for two years, augmented by funds from the committee for the Artists’ Ball and from Wunderlich Ltd., for whom he worked. He travelled to England where he enrolled at London’s Slade School of Fine Art but even with the scholarship’s financial support, living in the city was expensive and Dobell spent most of his time in conditions close to poverty. At first, he lived in ‘squalid little bed-sitting rooms in Bayswater and Pimlico.’1 One room he shared with a burglar named ‘Stiffy’ who used the bed in the daytime whilst his flatmate was at Art School.2

It was during these London years that Dobell truly became an important painter, able to capture the inner life of his subjects, a ‘humanity that is a little sombre in tone, a little uneasy... brilliant, but somehow disturbing.’3 The Slade recognised his talent and in 1930, awarded him first prize for figure painting with his Slade nude (Newcastle Art Gallery) and shared second prize for drawing. At the National Gallery, he avidly studied the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Soutine, Corot and El Greco, before visiting Holland, France and Belgium, where he found the artists of the Northern Renaissance, particularly Vermeer and Rogier van der Weyden, to be an inspiration. By the time of his return, the scholarship money had run out, but in late 1932 he was fortunate to be given the use of the studio of his New Zealand colleague, Fred Coventry, on the ‘top floor of a trace house in Westbourne Grove, Bayswater.’4 Before Coventry left to take up a commission, Dobell painted his portrait – arms folded, looking askance at the viewer, hair upswept and unruly – an early example of the artist’s finely intuitive portraits. More importantly, Dobell also painted his first masterwork here, The boy at the basin, 1932 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), which had started as a sketch for an unfinished image for the Slade from the previous year. Now transposed to Coventry’s studio, the rumpled, bare-chested figure in striped pyjama pants undertakes his morning ablutions, using a bowl of water set on a counter while the kettle boils on the flat’s single electric burner, a half bottle of milk and opened box of sugar to one side. It is a ‘a frozen moment in time, with the muted stillness of a Flemish interior’5 but has the attention to detail of straightened circumstance that would later be celebrated by the ‘Kitchen Sink’ movement which emerged in Britain in the late 1950s.

Besides Coventry, other Australian artists Dobell mixed with in London included Godfrey Miller, John Passmore and Arthur Murch. All (apart from the independently wealthy Miller) lived on low incomes and often supported each other; indeed, Young man sleeping was painted at a time where Dobell’s frugal living forced him to miss occasional meals whilst using ‘shoe polish on his legs to cover holes in socks.’6 In Young man sleeping, Dobell does not sensationalise such austerity; rather, he imbues the scene with the same refined sensibility as The boy at the basin. Technically, the sleeping figure is set at a diagonal which divides the picture plane, an angle emphasised further by the contrasting grey used for his suit and the shirt illuminated by white, scumbled brushstrokes. The overall design comprises a series of devices that cause the eye to roam across every detail, from the vertical stripes of the wallpaper carried through to the details on the headboard, and on to the irregular fringe of the bedspread. The figure’s left hand dangles by his side, the attenuated fingers mirrored in the upright struts at the back of the chair, and all is illuminated by the bedside lamp, the top of which has been adjusted to blaze solely on the model. This lighting is theatrical, likely informed by Dobell’s experiences as an extra in several London films in 1934. A comparison between Young man sleeping and The boy at the basin clearly illustrates the subdued tenor and masterly technique found in the very best of Dobell’s London paintings.

1. ‘William Dobell: an Australian genius’, People, Sydney, 21 June 1950, p. 42

2. ibid.

3. ibid., p. 44

4. Gleeson, J., William Dobell, Thames and Hudson, London, 1964, p. 33

5. Adams, B., Portrait of an art: a biography of William Dobell, Hutchison, Victoria, 1983, p. 66

6. Gleeson, 1964, op. cit., p. 39

ANDREW GAYNOR