(1914 - 1999)

Albert Tucker

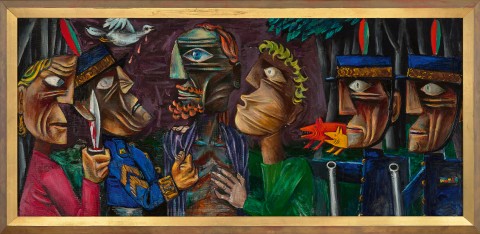

Betrayal, 1952

oil on composition board

Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Michael and Miriam Lasky, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1985

William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1999

Albert Tucker, Galleria ai Quattro Venti, Rome, 2 April – 2 May 1953

Mostra dei Pittori Australiani: Albert Tucker e Sidney Nolan, Associazione della Stampa Estera, Rome, 20 – 31 May 1954, cat. 1 (as ‘Tradimento’)

Albert Tucker, Bonython Art Gallery, Sydney, 28 October – 19 November 1969, cat. 93

Albert Tucker Paintings 1945 – 1960, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 1982, cat. 15 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Albert Tucker: A Retrospective, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 21 June – 12 August 1990 (label attached verso)

A Link and a Trust: Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan's Rome Exhibition, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 18 November 2006 - 20 May 2007, cat. 1 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, n.p.)

Albert Tucker: Marking the Past, Albert & Barbara Tucker Gallery, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 29 February – 16 August 2020

Uhl, C., Albert Tucker, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1969, cat. 8.3, pl. K, pp. 52, 56 (illus.), 98

Mollison, J. & Minchin, J., Albert Tucker: A Retrospective, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1990, p. 101 (illus.)

Fry, G., Albert Tucker, Beagle Press, Sydney, 2005, pp. 98 (illus.), 124, 239 (illus.)

When Albert Tucker painted Betrayal in 1952, he had been living and working in Europe for four years and had only just settled in the seaside village of Noli, located halfway between Nice and Genoa on the Italian coast. He was to remain there for ten months.1 While in Noli, Tucker began to read the Bible2, perhaps as a way in which to further both his knowledge and understanding of the stories he had been absorbing through the works of the Renaissance masters as he travelled through Italy. The artist responded deeply to the themes of birth, death and resurrection that he encountered in these works, and to their often graphic depiction, later recognising their correlation to the horrors he had seen during his time as an artist illustrator in the plastic surgery ward at Heidelberg Military Hospital.3 As he observed:

‘…they [‘all the kinds of mangled things’ in the plastic surgery ward] gave me images that I've fed on all my life. They appeared all later on. For example, see this one here… I developed that in Italy: all the gashes on all the paintings of the Christian martyrs. San Sebastian. The Virgin with a thousand swords going through her. Or San Sebastian perforated with arrows. Grünewald's Crucifixion, where you had Christ in a state of decomposition and simply decomposing on the cross, a horrific image with every wound, every gash.’4

Betrayal, 1952 was the first major painting Tucker created in Noli and his first Biblical subject.5 Judas’ betrayal of Jesus enabled the artist to tackle one of the central stories of Christian theology, and in doing so, to return to the examination of human values and morality that had underpinned his earlier Images of Modern Evil from 1943 – 48. In Tucker’s ambitiously modern version of the Kiss of Judas we see Christ and Judas in the Garden of Gethsemane at the moment of the betrayal, as Judas leans in to kiss Jesus, and thus reveal his identity. Both the central figures and the Roman guards that surround them, appear almost frieze-like, pushed to the front of the composition in a compression of space that creates a sense of danger and impending doom. The assembled group appear in profile, their craggy landscape-scarred faces and the glimpse of dark, abstracted background behind the figures providing a sense of the images yet to come – Tucker’s celebrated Antipodean Heads. The bright blues, reds and greens of the painting were unusual in the artist’s work at the time but similarly reappear later, in his images of the Australian bush after his return to Australia in 1960. Given that the long and troubling dialogue around John and Sunday Reed’s adoption of Tucker and Joy Hester’s son Sweeney was only resolved in the early 1950s6, the theme of betrayal was no doubt also one that the artist felt personally. Across his career, Tucker was open to drawing upon the wellspring of personal feelings in his work, and of using his practice as a means of ‘unloading the demons’:

‘…every painting you develop a kind of personal library, an iconography of the events in one's personal life, and these events would invariably come from traumatic experiences which one had had, but which, in going in the course of life there, these early traumas would be activated by, or triggered by, some element there which corresponded to it, and then the whole thing would come alive and feed the present experience. And so this was the thing I started using creatively as I became more and more aware of it…’6

Tucker exhibited Betrayal twice while in Europe, firstly in 1953, and then in Rome in 1954, alongside the work of his close friend and artistic rival, Sidney Nolan. After working somewhat in isolation as the Australian expatriate artist travelled through Europe, this exhibition served to introduce his work to European audiences, and importantly, to align Tucker’s practice with the broader interests of international modernism. The exhibition also appears to have been favourably received, with one Italian critic noting, ‘clear evidence of a cartoonist style in the Fortunato Depero fashion and a powerful sense of the monstrous in the style of Picasso, although a much more readable Picasso.’7 After visiting the exhibition, celebrated Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico – whose work Tucker greatly admired – invited him to attend his ‘Sunday Soirées’, whose carefully selected guest list included aristocracy and leading philosophers of the time.8 This positive development was closely followed by Tucker’s representation at the Venice Biennale in 1956, and the acquisition of his work by the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1958 (see lot 12).

1. Burke, J., Australian Gothic: A Life of Albert Tucker, Knopf, Milsons Point, 2002, p. 325 – 26

2. ibid., p. 328

3. Transcript of Robin Hughes interview with Albert Tucker, 14 February 1994, Australian Biography: Albert Tucker, National Film and Sound Archive, see: https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/asset/99512-australian-biogra..., (accessed 21 July 2025)

4. ibid.

5. Burke, op. cit.

6. Albert Tucker’s first wife, artist Joy Hester, left Tucker for artist and poet, Gray Smith, in 1947. When Tucker travelled abroad in October of that year, he left their young son Sweeney in the care of John and Sunday Reed, who later adopted him.

7. Albert Tucker: Reading the Past, VCE Art: Unit 4, Outcome 1, p. 8, Heide Learning, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 29 February 2020 – 14 March 2021, see: https://wp.heide.com.au/app/uploads/2022/10/920.AlbertTucker_MarkingTheP... (accessed 22 July 2025)

8. Hambur, M., Albert Tucker: The Modern Metaphysical, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2022, see: https://wp.heide.com.au/app/uploads/2023/05/1034.Albert-Tucker_Modern-Me... (accessed 22 July 2025)

KELLY GELLATLY