(1920 - 2001)

Robert Klippel

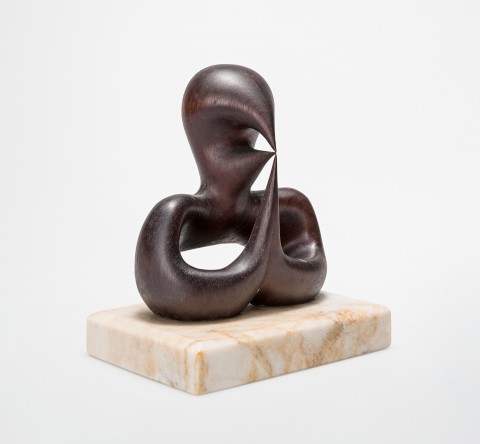

No. 21, Pointed theme, 1945

Tasmanian blackwood

Richard and Joan Crebbin Collection, Sydney, acquired directly from the artist

Joan Crebbin, Sydney

Deutscher and Hackett, Sydney, 30 November 2016, lot 3

Private collection, Sydney

Robert Klippel: a tribute exhibition, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 9 August – 13 October 2002

Gleeson, J., Robert Klippel, Bay Books, Sydney, 1983, pl. 22, pp. 23, 26 (illus.), 462 (as 'Opus 21 'Pointed Theme'')

Edwards, D., Robert Klippel, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002, pp. 22 (illus.), 23, 25 (illus.), 246

Edwards, D., Robert Klippel: Catalogue Raisonné of Sculptures, (CD-ROM), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002, no. 21 (illus.)

The sensuously carved, semi-abstract No. 21, pointed theme, 1945, is an exceptionally accomplished early work by Robert Klippel, one of Australia’s greatest sculptors. Carved from Tasmanian Blackwood and based on a tripartite trefoil structure, the sculpture tapers to three thorn-like points converging in the centre but not touching, hopefully suspended. Exploring the tension between absolute abstract forms and the emotional valence of figuration, No. 21, pointed theme belongs to a group of small carved works made in Sydney immediately at the end of World War II. These were Klippel’s first forays into fine art before matriculating at East Sydney Technical College and leaving for London in 1947.1 Through the influence of the poet Pam Broad, Klippel’s artistic course was shaped by early exposure to Modern British art, literature and poetry, and these carvings, particularly No. 21, pointed theme, reflected his absorption of their ideas on pure form, nature and creativity, prefiguring the investigations he would make into degrees of abstraction in London.2

Numbered 21 in the chronological sequence of the artist’s original sculptures (biographer James Gleeson noting that the first eight were effectively copies of existing artworks), No. 21, pointed theme was made early in the artist’s career, joining a group of hand-carvings centred around the human form, specifically the standing figure.3 In No. 21, pointed theme, the tripartite structure corresponds to a figure’s torso, its hands lifted to the face in a gesture of prayer, albeit radically simplified and smoothed, tending towards pure formal abstraction. Figuration was a field of exploration that the artist was soon to abandon, writing in his notebook the same year that ‘sculpture must be revolutionised without the figure.’4

The simplified structure of No. 21, pointed theme featuring a dynamic, interlocking arrangement of curved and pointed vectors in three dimensions was developed in three drawings dated between 16 – 19 June 1945.5 Carved on an intimate scale, redirecting his expert craftsmanship of wood honed by years of model ship-making for the Australian Navy during the Second World War, No. 21, pointed theme is defined by the juxtaposition of the sensuously smoothed forms and the graphic tension of the points almost meeting. Carved and pierced, with complex interiors defined by negative space, the sculpture shares similarities with early carvings by the British artist Barbara Hepworth. It also bears a striking resemblance to Three points, an abstract sculpture conceived in lead by Henry Moore in 1939 – 40 and later cast in bronze. Gleeson, however, notes that the artist only came across a photograph of this work after he had investigated the same visual theme in the drawings of June 1945 and would not be deterred from arriving at his own sculptural resolution.6 Interestingly, although Moore’s sculpture appears entirely abstract, it was based on the ‘emotional and physical or physical action in it where things are just about to touch but don’t. There is some anticipation of this action’, one source of his inspiration reportedly having been the pinching action central to the famous School of Fontainebleau painting of Gabrielle d’Estrées and her sister in the Louvre.7

Klippel’s No. 21, pointed theme – joining emotive figurative carvings No. 9 anguish and No. 11 grief, both completed in 1944 – is amongst Klippel’s most self-expressive works, reflecting heightened mental states, likely related to the profound loss of the artist’s brother John, a pilot declared missing in action in May 1944 and presumed dead in May of the following year.8

1. Edwards, D., Robert Klippel, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002, p. 23

2. Klippel, cited in Gleeson, J., Robert Klippel, Bay Books, Sydney, 1983, p. 16

3. ibid., p. 18

4. Klippel, cited in Edwards, op. cit., p. 19

5. Gleeson, op. cit., p. 23

6. ibid., p. 17

7. Sylvester, D., Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, 1968, p. 36

8. ‘John Owen Klippel (1921 – 1944)’ in People Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University at https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/klippel-john-owen-21877 (accessed 10 June 2025)

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH