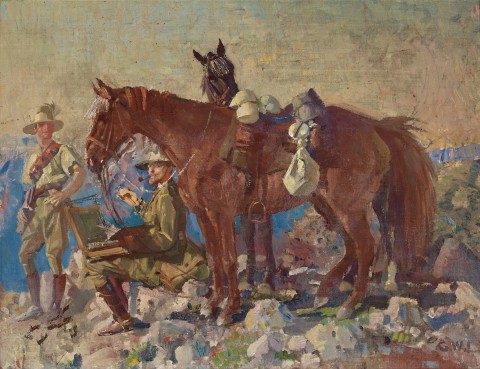

ARTIST AND HIS BATMAN, LIGHT HORSE CALVARY, JERUSALEM HEIGHTS, 1920

GEORGE LAMBERT

oil on canvas on plywood

31.5 x 42.0 cm

signed with initials lower right: G. W. L

Private collection

Sir Edward Hayward, Adelaide

Old Clarendon Gallery, Adelaide (label attached verso)

Private collection, Adelaide, acquired from the above in November 1982

Thence by descent

Private collection, Adelaide

Royal Visit Loan Exhibition of Australian Paintings, National Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide,1954 (label attached verso)

Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 66 (label attached verso, as ‘Light Horse Cavalry, Jerusalem Height’)

George Washington Lambert, S.H Ervin Museum and Art Gallery, The National Trust of Australia, Sydney, 22 August – 8 October 1978, cat. 41 (as ‘Australian Light Horse on the hills above Damascus’)

Old Clarendon Gallery, Adelaide, 1982 (as ‘Portrait with Horses’)

Gray, A., George Lambert 1873–1930: Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculpture, Drawings in Public Collections, Bonamy Press, Perth, Sotheby's Australia and Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1996, cat. P356, p. 95 (as ‘The artist and his batman’)

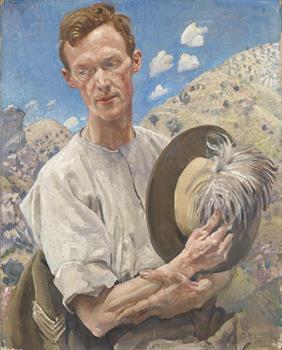

The official artist (Self Portrait), 1921, oil on canvas, 91.7 x 71.5 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

1112.jpg

When the First World War erupted, George Washington Lambert was aged forty and resident in Britain. A society painter of some renown, his equestrian portrait of Edward VII (1910) was considered by many as the best ever done of the monarch. Now considered an equal in London’s art world, Lambert had actually spent his formative years working on a sheep property at Warren in far-western New South Wales and remained in his heart a ‘country man’ with a great love of horses and abiding respect for people who worked the land. In late 1917, he was commissioned to be Australia’s sole war artist in Palestine, and through this ‘the war was to release the man of action that slumbered in Lambert. Always a keen observer, he was by this a splendidly trained draughtsman capable of painting equally well men, horses and landscape, and the incidents of war – the ideal man for Palestine.’1 Artist and his batman, Light Horse Cavalry, Jerusalem Heights, 1920, is a self-portrait as personal souvenir, one redolent of his experience embedded with the troops.

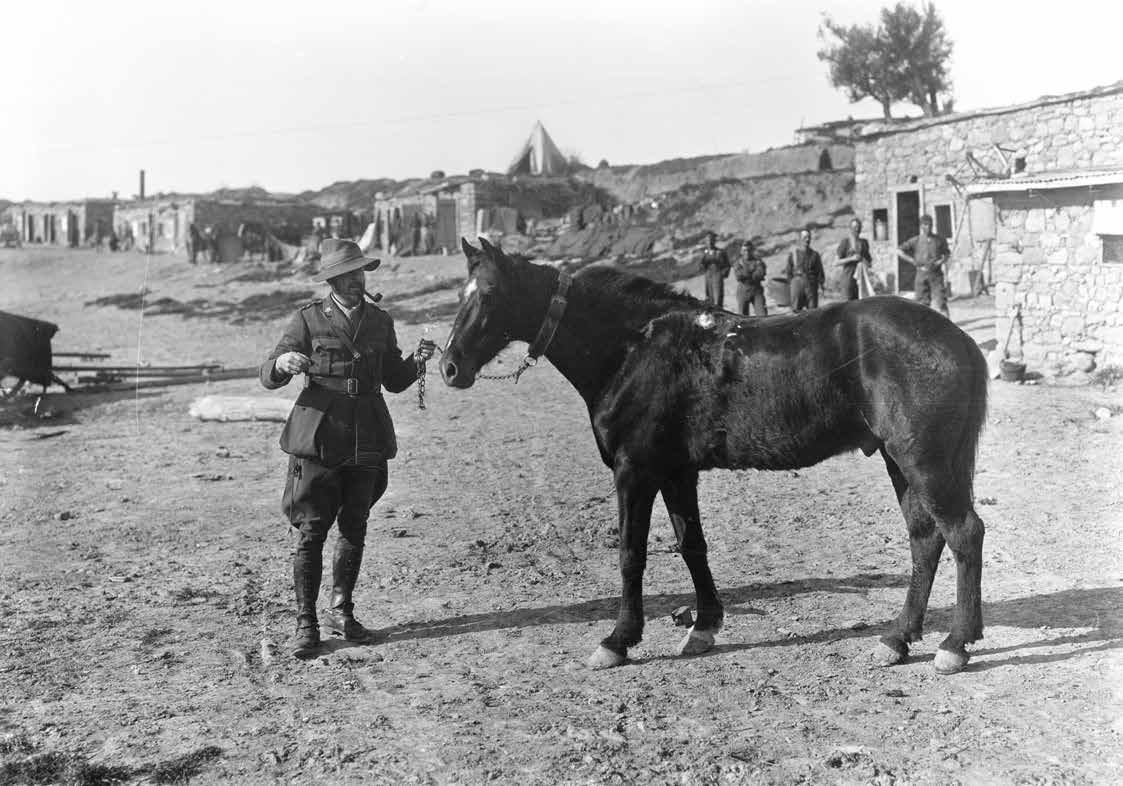

Due to his age, Lambert was unable to enlist for the Australian Imperial Force, so he joined a voluntary unit called the United Arts Rifles, where he trained recruits in horsemanship. Following the appointment as war artist, he travelled to Palestine where the Light Horse Brigade was engaged in fighting the Turkish forces. On Christmas Day, ‘complete with a Light Horseman’s plumed hat, spurs, leggings and honorary commission as Lieutenant’, Lambert sailed for the Palestine front and disembarked in Alexandria three weeks later.2 The artist was dazzled by the blazing light which played over the jagged landscape, and soon recognised in the ‘“sweating, sun-bronzed men and beautiful horses” of the Light Horse, the pioneer bushmen he had observed working the wool trade (on) his uncle’s property at Warren.’3 Many of Lambert’s new companions were veterans of the Gallipoli campaign, and with their guidance and vivid stories, he moved from Egypt through to Syria and Palestine, producing forty-nine oil sketches and nearly a hundred drawings, as well as several sketchbooks filled with small pencil studies by the end of the three-month commission.

DH2021 Verco ART Cat (December) - Cat 06 FA.jpg

In early 1919, Lambert was the only artist invited to join the historian Charles. E. W. Bean on the first official mission to visit Gallipoli since the ANZAC forces had evacuated. He again produced many images but also revealed his strength of character when he and others of the party were ‘forced to bury more than 300 bodies in a strip of land the size of three tennis courts [at The Nek], which prompted Lambert to write to his wife that “gruesome is scattered all over the battlefield... evidence grins coldly at us non-combatants and I feel thankful that I have been trained to stop my emotions at the border line.’’’4 He then re-visited Palestine and Syria, painting more preparatory studies as he again stayed with the Light Horse whilst they demobilised.

On return to London, Lambert set to work creating large paintings based on his sketches, armed with new understanding of the true horrors of war. Numerous of these are now star attractions at the Australian War Memorial, such as The charge of the Australian Light Horse at Beersheba 1917, 1920; ANZAC, the landing 1915, 1920-22; and The charge of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade at the Nek, 7 August 1915, 1924. However, it is in the smaller, more intimate works painted at the same time that Lambert truly expressed himself, celebrating the camaraderie experienced amongst his fellow horsemen. Artist and his batman, Light Horse Cavalry, Jerusalem Heights is one of these and its sense of immediacy is striking. Jerusalem is set on a plateau 785 metres above sea level, with views overlooking the Dead Sea, the biblical Mountains of Moab, and coastal plains that march west toward the Mediterranean. It was territory Lambert knew intimately, having ‘camped for a time during the fierce heat of the summer of 1918 in Chauvel’s Desert Mounted Corps camp at Talaat ed Dum [just north of Jerusalem], in the hideous country of the Wilderness, and from there, and from the Light Horse camps down in the stifling Jordan Valley, he would walk out day after day for hours at his labour of love.’5 In this self-portrait, painted in the London studio, Lambert’s delight is obvious, seated with his portable paint box in this harsh land amongst the horses and men he so admired, his smiling face and favourite pipe accentuated by the curved loop of the white bridle. His batman, who has not been identified, wears the Light Horse emblem of an emu feather in his hat and was an essential companion in Palestine, being a soldier assigned to act as a servant to commissioned officers and who also looked after their horse (known as the bat-horse).6

210837.jpg

Lambert returned to Australia in 1921 and was to enjoy another decade of success in Australia and Britain, but his experiences in the Middle East remained some of his happiest memories. He actively re-engaged with the Australian art community and was important in his advocacy and support for a number of younger artists. Horses, however, remained his greatest love and it was after a ride in May, 1930, as he leant over to fix a piece of timber to his mount’s drinking trough, that this grand cavalier died of a heart attack. Arthur Streeton was devastated to lose his old friend, writing to Basil Burdett that ‘it’s difficult to get the horrible news out of one’s head – it’s quite useless to fret about him. But everything here reminds me of him ... poor old Julian Ashton will feel it, he was always so proud of G. W. L.’7

1. Lindsay, L., ‘George Lambert – our first Australian master’, Art in Australia, 3rd series, no.36, February 1931, p.15

2. Roberts, Major M. L. H., ‘George Washington Lambert’, The Australian Light Horse Association, www.lighthorse.org.au/george-washington-lambert Viewed 12 October 2021

3. Yip, A., ‘George Lambert at Gallipoli. ‘A wonderful setting for the tragedy’: an artist captures the Anzac horror’, Look magazine, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2013, pp.10-11

4. Ibid.

5. Gullett, H.S., ‘Lambert and the Light Horse’, in: Art in Australia, ‘Lambert Memorial Number’, 3rd series, no.33, August-September 1930

6. Charles Bean recorded that Lambert was assigned a Light Horseman named (William?) Spruce from Port Stephens, NSW, to handle the mule the artist used to carry his supplies in Gallipoli, but there is no record that Spruce was also with Lambert in Palestine. The author thanks Hollie Gill at the Australian War Memorial for this information.

7. Arthur Streeton, letter to Basil Burdett, 31 May 1930. Transcribed in: Galbally, A., and Gray, A., Letters from Smike: the letters of Arthur Streeton 1890-1943, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989, p.196. Between 1895 and 1899, Lambert studied with Julian Ashton who always remained proud of student’s achievements.

ANDREW GAYNOR