THE BATH, 1996

JOHN OLSEN

oil on canvas

180.0 x 200.0 cm

signed and dated lower right: John / Olsen / 96

Olsen Carr Art Dealers, Sydney (stamped on stretcher bar verso)

Private collection, Sydney, acquired from the above in 1998

John Olsen 1993 – 1998, Olsen Carr Art Dealers, Sydney, 7 – 25 April 1998, cat. 15

John Olsen: The You Beaut Country, The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia at Federation Square, Melbourne, 16 September 2016 – 12 February 2017; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 10 March – 12 June 2017

Masterpieces of Australian Painting, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney, 2 – 27 February 2021

John Olsen: Goya’s Dog, National Art School Gallery, Sydney, 11 – 26 June [suspended due to covid]; 29 October – 27 November 2021; Ngununggula, Southern Highlands Regional Gallery, New South Wales, 26 March – 15 May 2022

McDonald, J., ‘Masterpiece? I’ll let you know in 500 years’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 18 April 1998, p. 14

Smee, S., ‘Worlds apart’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 17 April 1998, p. 58

Auty, G., ‘Grasping the subject’, Weekend Australian, Sydney, 11 – 12 April 1998

Hart, D., John Olsen, 2nd ed., Craftsman House, Sydney, 2000, pl. 157, pp. 228, 230 – 231 (illus.), 234, 256

Hurlston, D., and Edwards, D., (eds.), John Olsen: The You Beaut Country, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2016, pp. 61 – 62, 165 (illus.), 208

McDonald, D., ‘Culture Buff: John Olsen’, The Spectator Australia, Victoria, 22 April 2017

Alderton, S., Norton, K., Wolifson, C. and Wright, B., Goya’s Dog, National Art School, Sydney, 2021, pp. 100, 101 (illus.) 145

McDonald, J., ‘King-of-bright John Olsen reveals his dark and melancholy side’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 18 June 2021

The bath – Birdsville Bunny and Pointer, 1997 – 98, oil on canvas, 137.5 x 183.0 cm, private collection, Queensland, illus. in Alderton, S., ibid, pp. 98 – 99

The Bath, 1998, oil on canvas, 120.0 x 140.0 cm, private collection

The Bath: Early Morning, Bondi, 2007, oil on linen, 130.0 x 184.0 cm, private collection, New South Wales

We are grateful to Kylie Norton, Editor, John Olsen Catalogue Raisonné, for her assistance with this catalogue entry.

230136 HIGH RES cmyk FA.jpg

With a vast and varied oeuvre spanning more than seven decades, John Olsen has quite deservedly been hailed as Australia’s greatest living artist. From the pulsating, larrikin energy of his You Beaut Country series, to the quieter, more metaphysical paintings inspired by his expeditions to Lake Eyre, or the exquisitely lyrical works immortalising his halcyon days in Clarendon, Olsen’s unique interpretations of the natural environment in its manifold moods have become indelibly etched on the national psyche. Embracing both figuration and abstraction, his signature technique fusing painting and drawing as one reveals the hand and eye of the artist with every stroke – the act of creation thus imbuing the painted surface with a powerful sense of the artist’s own irrepressible energy and palpable joie de vivre. As Deborah Hart, curator and author of several authoritative publications on the artist, asserts, ‘Olsen has confronted and helped redefine our basic conception of landscape… providing a psychological encounter with place, not only as seen but as experienced, resulting in a fresh, exhilarating vision.’1

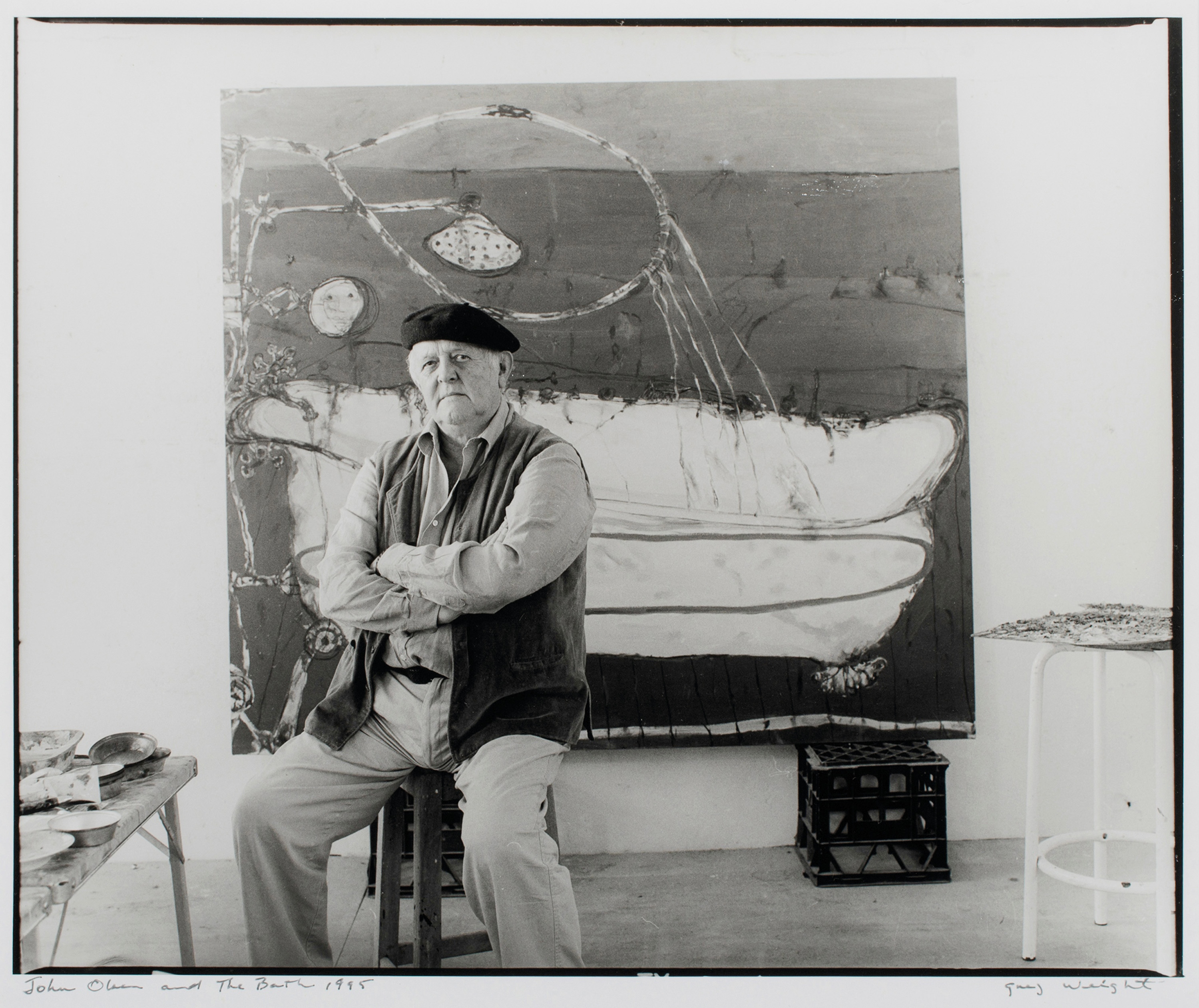

Universally recognised as one of the artist’s most impressive works, significantly The Bath, 1996 was created during a particularly challenging chapter of Olsen’s life. As Ken McGregor and Jenny Zimmer elucidate, his mother had died the year prior in 1995, and throughout the decade more generally he had witnessed a succession of artist friends decline and pass away – an experience that inevitably prompted a reckoning with his own mortality. Around this time, Olsen’s knees also deteriorated, and accordingly, he underwent the first of several operations necessitating a less active life ‘confined to base: kitchen, bed and bath.’2 Serendipitously perhaps, such physical setback would become the impetus for one of the most career-defining images by Australian photographer, Greg Weight – John Olsen in Bath, Rydal, New South Wales, 1996 (National Portrait Gallery, Canberra) – created the same year as the present painting. Weight recalls,

‘I went to see him near Bathurst where he used to live and he explained that his knees weren’t working very well, and that he was spending a fair bit of time either in the bath or in bed. I’d photographed him before as we’d known each other for a long time. I saw that bathroom and it was just so photogenic – the whole atmosphere was incredible, and I suggested he hop in the bath. We began to parody a painting done by the French artist Jacques-Louis David, called The Death of Marat. We both realised what we were doing, and it accounted for the humorous expression on John’s face. Marat was a French revolutionary who was killed in the bath and because John himself is a revolutionary, he didn’t mind. He enjoyed the humour and the reference of the portrait, and we ended up putting it on the cover of my book.’3

2004.106_John_Olsen_Bath_cmyk_FA.jpg

That Olsen should here invoke his French Neoclassical predecessor is hardly surprising, for his oeuvre is typically rich in allusion and inference gleaned from the canon of art history. Certainly, in considering his various iterations of the bath motif during this time it is difficult not to draw comparison with the intimate domestic scenes of French post-impressionist and founding member of Le Nabis, Pierre Bonnard – an artist much admired by Olsen whose delicacy of touch and radiant colour was no doubt a salient influence upon watercolours such as the seminal The Bath, 1995 (private collection) in particular. More specifically, The Bath, originally titled The Absence of Venus, directly refers to Florentine Renaissance painter, Sandro Botticelli’s iconic Birth of Venus, c.1480 (The Uffizi, Florence), in which an angelic nude Venus floats upon a seashell surrounded by delicate flowers. As Hart continues, ‘In Olsen’s work, the ivory bath with scalloped feet is a kind of shell, although it is far removed from Botticelli’s idealised conception. Instead in search of a more robust beauty, Olsen has transmuted the old-fashioned bath at Rydal into an open landscape; the creamy white of the receptacle residing in the rich dark brown earth against a high horizon line.’4

Having moved to Rydal, near Bathurst in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales with his wife Katharine in March 1990, for Olsen the sight of abandoned tubs on country properties would not have been uncommon – as evidenced by their prevalence in the bucolic farmyard scenes of his contemporary Bill Robinson, see lot 21. Here however, the discarded vessel transcends the mundane to evoke analogy with Olsen’s experience at Lake Eyre: ‘…in the sense of fullness and emptiness; the water filling the vessel and draining away (in this instance, rushing out of the open plug hole). As the artist wrote many years previously, ‘Remember the Tao. A jug is made of clay but the use of the jug is in its emptiness’.’5 Elaborating further upon such resonances, Hart suggests the bath takes ‘…on the impression of a dream – as though aspects of its former existence in a domestic setting had come to revisit it. A face, a round like a moon, appears in the shaving mirror, while the showerhead and rail above are props that suggest the potential of bringing forth a shower. All is held in a poignant state of balance.’6

Imbued with myriad meaning, alongside the artist’s inimitable verve and playful wit, indeed The Bath is a masterwork that encapsulates Olsen at his finest. Incidentally, Olsen similarly regarded the work among his best at the time of its creation, writing in his journal: ‘11 June 1996: The Bath might be my best since Donde Voy. Old bath, rusted with different tonalities, taken from the bath in the Rose Room…’7 Such would also accord with the sentiments of Deborah Hart, co-author of the catalogue accompanying the artist’s acclaimed survey exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2017, who describes The Bath as ‘one of Olsen’s most memorable works’8, while art critic John McDonald went so far as to proclaim it ‘arguably the best painting in the show…’, eloquently adding ‘The visual echoes impart a liveliness to the scene that could be banal in other hands. As usual with Olsen’s best work, there is a restless, fidgety feel to the brushwork, as though marks were popping up spontaneously all over the painting.’9

1. Hart, D., John Olsen, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2000, p. 207

2. McGregor K. & Zimmer, J., John Olsen: Journeys into the ‘You Beaut Country’, Thames & Hudson, Melbourne, 2016, p. 12

3. Greg Weight, cited in Wulff, A., ‘Photographer Greg Weight reveals the seven portraits that defined his career’, Vogue Living,14 August 2020, at https://www.vogue.com.au/vogue-living/arts/photographer-greg-weight-reve... (accessed 31 March 2023)

4. Hart, op. cit., p. 228 & 232

5. Ibid.

6. Hart in Hurlston, D. and Edwards, D., John Olsen: The You Beaut Country, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2017, p. 61 – 62

7. The artist’s journal, 11 June 1996 (the author is most grateful to Kylie Norton, editor of the upcoming John Olsen Raisonné, for bringing this entry to her attention). Notably, the dark brooding Donde Voy? Self Portraits in Moments of Doubt, 1989 was the subject of yet another Archibald Prize controversy when despite prevailing predictions, the work did not win.

8. Hart, 2000, op. cit., p. 228

9. McDonald, J. ‘Masterpiece? I’ll let you know in 500 years’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 18 April 1998, p. 14

VERONICA ANGELATOS