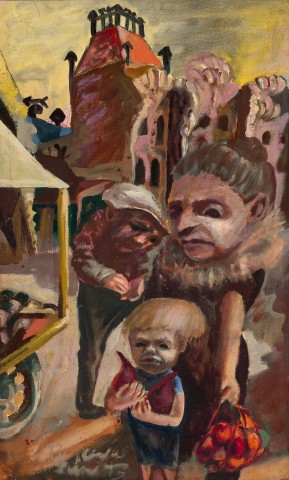

BOY BESIDE A FRUIT BARROW, 1943

JOHN PERCEVAL

oil on canvas on composition board

69.0 x 42.0 cm

signed and dated lower left: Perceval / Jan 43

bears inscription with title on handwritten label verso: Boy by the Fruit Barrow / 1943

Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in April 1979

Rebels and Precursors, Aspects of Australian Painting in Melbourne 1937 – 1947, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, August – September 1962; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, September – October 1962, cat. 90 (as ’Boy on the Fruit Barrow’)

John Perceval Canberra Exhibition, ANU and Department of Interior, Albert Hall, Canberra, 13 – 24 July 1966, cat. 12 (label attached verso, as ‘Boy by the Fruit Barrow’)

Autumn Exhibition 1979, Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne, 5 – 20 April 1979, cat. 105 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

John Perceval: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 30 April - 12 July 1992 and Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 6 August - 20 September 1992 (label attached verso)

On long term loan to the Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria, 2005 – 2023

Plant, M., John Perceval, Lansdowne Press, Victoria, 1978, pl. 3, pp. 16, 17 (illus.)

Haese, R., Rebels and precursors: the revolutionary years of Australian art, Penguin, Victoria, 1981, p. 204

Allen, T., John Perceval, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 1992, pp. 140, 141, (illus.), 146

230074 placeholder boy with broken pot cmyk FA.jpg

John Perceval was the youngest member of the group of artists forever known as the Angry Penguins. They gained this collective title during World War II through their association with Max Harris’ magazine of the same name, and further benefited from the patronage of John and Sunday Reed at Heide. The Angry Penguins each created momentous series of artworks in the years 1942 – 1944: Albert Tucker with the harrowing Images of Modern Evil; Sidney Nolan and his acclaimed paintings of the Wimmera; Arthur Boyd’s twisted scenes of Melbourne populated by gargoyles and cripples; and Joy Hester with her emotive and lyrical ink-wash drawings. In many ways, the most intimate and psychologically complex were John Perceval’s images of a small, blonde child with a bowl haircut navigating landscapes of personal memory. This child was the artist himself, trawling through events from his troubled childhood located within a setting of pre-war Melbourne. Boy beside a fruit barrow, 1943, is a significant work from the series and one of the few remaining in private hands.

To say that Perceval had a difficult childhood is a major understatement. Born Linwood Robert Stevens South, he and his older sister Betty were initially raised on large wheat property ‘Illamurta’ 220 kilometres east of Perth, near Bruce Rock. Perceval’s parents’ marriage failed soon after his birth and his mother moved to Perth. As an act of early defiance and self-invention, the young boy rejected his given name and began using ‘John’ instead. At the age of five, he and his sister re-joined their mother in Perth and it was here that he first gained encouragement for his art. Three years later, the children again returned to ‘Illamurta’ and the harsh realities of life on a working farm became part of the boy’s daily routine. In the interim, his mother married William de Burgh Perceval. Betty and John, now aged 11, moved again to join them and he adopted Perceval as his surname. In late 1937, however, he contracted the crippling disease of polio, leading to a year bedridden in hospital, followed by a long rehabilitation. His latent talent was recognised by visiting journalist who wrote a large article for The Sun, headlined ‘Paralysed boy of 15 paints like a master’, and illustrated with a powerful self-portrait.1 This painting is now one of the treasures in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria.

230074 placeholder Boy with Cat 2 cmyk FA.jpg

The first connected series that Perceval completed included the extraordinary Boy with cat I and II, 1943, where, as Bernard Smith described, ‘the child becomes…a figure of pity and terror’2 as the cat’s claws tear into his flesh. The series progressed and other characters started to appear as Perceval recalled specific childhood episodes of himself in a wheelchair being guided through the streets, encountering vaudeville side shows of performing dogs and circus entertainers on stilts. Seen together, these images portray a haphazard, dystopian carnival, whose participants leer over the boy as he navigates his way through the world. Boy beside a fruit barrow connects directly to these, and Perceval’s biographer Margaret Plant vividly describes its tension with ‘the fair-haired child, small in front of a huge mother figure with hair in a chignon and her arm taut with the weight of her purchases; and the fruit man, hunched up and fingering the money. Behind the three hollow-eyed figures is a Caligari set of tall houses with windows black and vacant like the people’s eyes.’3 It is a powerful and compelling scene, one which underscores Perceval’s belief that ‘children are the real world.’4

230074 cmyk FA.jpg

Perceval’s ‘childhood’ paintings from 1943 may be found in major Australian collections including the National Gallery of Australia; National Gallery of Victoria; Heide Museum of Modern Art; and the Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania. Together with Boy beside a fruit barrow, they are now regarded as a pivotal and critically important sequence in Australian art of the 1940s.

1. Pimlott, F.L., ‘Paralysed boy of 15 paints like a master’, The Sun News Pictorial, Melbourne, 25 June 1938, p. 43

2. Bernard Smith, cited in Reid, B., Of Light and Dark: the art of John Perceval, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1992, p. 14

3. Plant, M., John Perceval, Lansdowne Press, Victoria, 1978, p. 16

4. The artist, cited in Reid, B., ibid., p. 3

ANDREW GAYNOR