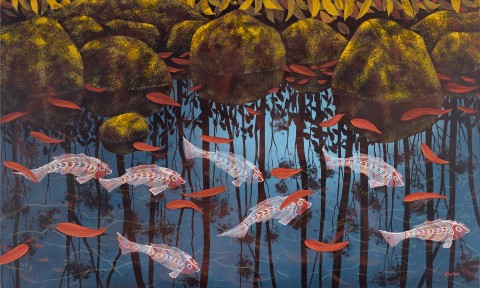

GUYI RIRRKYAN (FISH AND ROCKS), 1990

LIN ONUS

synthetic polymer paint on canvas

91.5 x 151.5 cm

signed lower right: Lin Onus

bears inscription with title verso: GUYI RIRRKYAN

Painters Gallery, Sydney

Private collection, Melbourne

Paintings and Sculpture by Lin Onus, Painters Gallery, Sydney, May – June 1990

Described by curator Margo Neale as a ‘cultural terrorist of gentle irreverence’1, Lin Onus today remains acclaimed for his unique ability to challenge cultural hegemonies with subtlety and sophistication through his distinctive hybrid style that integrated Indigenous spirituality and narrative with Western representational systems. Of both Yorta Yorta and Scottish descent, not only did Onus straddle a rare cusp in cultural history between millennia, but rather than resolve such differences through fusion, he sought to span the divides - expanding the parameters of post-colonialism to incorporate the Indigenous voice. Infiltrating issues of Aboriginality into everyday Australian experience, thus Onus’ artistic achievements rely upon inclusion rather than alienation for their impact, poignantly embodying his aspirations for healing and reconciliation more broadly: ‘I hope that history might see me as some sort of bridge between cultures…’2

Of particular relevance to his celebrated ‘water and reflection’ paintings such as the impressive Guyi Rirrkyan (Fish and Rocks) 1990 featured here, were Onus’s regular spiritual pilgrimages to Arnhem Land which, he later mused, gave him ‘back all the stuff that colonialism had taken away.’3 As Neale observes, ‘…now, in addition to his own ancestral site at Barmah forest he was permitted to access new sites of significance such as Arafura Swamp, or his adoptive community at the outstation Garmedi; to kinship systems in which he and his family were assigned skin names; to language that he used for many of the titles of his works; to ceremony and Dreaming stories.’4 Arguably most influential upon his stylistic evolution, however, was the relationship he fostered in Arnhem Land with the highly esteemed Aboriginal painter who became his adoptive father and mentor, Jack Wunuwun. Admiring the older artist’s rarrk technique (cross-hatching designs) – exemplified by his important bark painting of a transparent fish-trap Barnumbirr the Morning Star, 1987 in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra - Onus subsequently embarked upon his highly acclaimed series of watery landscapes which, rich in reflections and ambiguities, substitute the traditional European panoramic view for one described by his mentor Wunuwun as ‘seeing below the surface.’

Mesmerisingly beautiful in its technical virtuosity and aesthetic power, Guyi Rirrkyan (Fish and Rocks) 1990 offers a stunning example of the way in which Onus sought to portray the landscape as a ‘cultural archive’ – a repository of myth, history and ideology. Exuding a dream-like ‘otherworldliness’, the composition features the artist’s signature motif of ‘indigenised’ fish decorated in rarrk, swimming between exquisitely rendered layers of fallen russet-coloured leaves and the reflections of tall spindly gum trees on the waterhole surface. Significantly, such emphasis upon reflection and water surface in these mature, more resolved works has been recently perceived as ‘a call for deep consideration of one’s experience of life, or more specifically, to make connections between oneself and the world.’5 A poetic yet potent statement of cultural authority - of Onus’ Indigenous understanding of that which ‘lies beneath the surface of things’6 - indeed the work encapsulates well the artist’s declaration that there is no distinction between the political and the beautiful. As Neale elucidates, considering the multifaceted meaning of such works, ‘…they are deceptively picturesque, for things are not always what they seem. Laden with cross-cultural references, visual deceits, totemic relationships and a sense of displacement, they, amongst other things, challenge one’s viewing position: Are you looking up through water towards the sky, down into a waterhole from above, across the surface only or all three positions simultaneously?’7

1. Neale, M., Urban Dingo: The Art of Lin Onus 1948–1996, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2000, p. 67

2. Lin Onus, artist statement, 1990

3. Onus cited Neale, op.cit., p. 15

4. ibid., p. 15 – 16

5. Lindsay, F., Lin Onus: Yinya Wala, Mossgreen, Melbourne, 2016, p. 3

6. Sequeira, D, Lin Onus Eternal Landscape, Margaret Lawrence Gallery, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, 2019, n.p.

7. Neale, M., Lin Onus, exhibition catalogue, Savill Galleries, Melbourne, 2003, p. 1

VERONICA ANGELATOS