Night stop, Bombay, 1981

Jeffrey Smart

oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas on board

100.0 x 100.0 cm

signed lower right: Jeffrey Smart

Jeffrey Smart, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 26 October – 7 November 1981, cat. 1

Jeffrey Smart – Recent Paintings, Redfern Gallery, London, 11 November – 4 December 1982, cat. 4

Jeffrey Smart, Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Sydney, 5 – 16 April 1983, cat. 12

The Jack Manton Exhibition 1989: recent works by twelve Australian artists, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 12 July – 27 August 1989

Jeffrey Smart, Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, 23 October – 20 November 1992, cat. 8

Jeffrey Smart Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 27 August– 31 October 1999, cat. 63, and touring to the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 26 November 1999 – 6 February 2000; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 10 March – 21 May 2000; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 10 June – 6 August 2000 (label attached verso)

Jeffrey Smart 1921 - 2013: Recondita Armonia – Strange Harmonies of Contrast, University Art Gallery, University of Sydney, Sydney, 2 November 2013 - 7 March 2014, cat. 10

Jeffrey Smart, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 11 December 2021 – 15 May 2022

Redfern Gallery advertisement, Art International, Lugano, vol. XXV, no. 7-8, September - October 1982, back cover (illus.)

Malouf, D., 'Jeffrey Smart - Recent Work', Art International, Lugano, vol. XXV, no. 9-10, November - December 1982, p. 67 (illus.)

Smith, M., ‘Jeffrey Smart: optimistic in the age of the bomb’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 1 April 1983, p. 24 (illus.)

Quartermaine, P., Jeffrey Smart, Gryphon Books, Melbourne, 1983, pp. 60, 91, 92, 94 (illus.), 117

McDonald, J., Jeffrey Smart. Paintings of the 70s and 80s, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990, pp. 39, 160

Capon, E., Jeffrey Smart Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, cat. 63, pp. 160 (illus.), 210

Capon, E., Jeffrey Smart Drawings and Studies 1942 – 2001, Australian Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2001, fig. 27, p. 108 (illus.)

Pearce, B., Jeffrey Smart, The Beagle Press, Sydney, 2005, pl. 165, pp. 164, 165 (illus.), 255

Allen, C., Jeffrey Smart Unpublished Paintings 1940 – 2007, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 2008, pp. 31, 32 (illus.)

FitzGerald, M., ‘Malouf makes Smart choices’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 6 November 2013 (illus.)

Farrelly, E., ‘Smart art merits place among nation's greats’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 14 November 2013

Malouf, D., ‘Our Second Nature,’ Muse, University of Sydney, Sydney, issue 6, November 2013, p. 1 (illus.)

Pearce, B., Master of Stillness: Jeffrey Smart, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2015, revised edition, p. 18 (illus.)

Hart, D., and Edwards, R., Jeffrey Smart, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2021, pp. 40, 43 (illus.), 69, 163

This work will be accompanied by

Jeffrey Smart, Sketch, 1981 for Night stop, Bombay, 1981,

pencil on paper, 17.5 x 23.0 cm

We are grateful to Stephen Rogers, Archivist for the Estate of Jeffrey Smart, for his assistance with this catalogue entry.

1.jpg

Jeffrey Smart was a true painter of modern life, finding arresting beauty in the crisp outlines of the built environment and the prosaic icons of an urban existence. Reflecting on this choice of subject matter and its harmonious marriage with contemporary styles of painting, as early as 1969 Smart declared, ‘I find myself moved by man in his new violent environment. I want to paint this explicitly and beautifully [...] how wrong a jet plane or a modern motor car looks painted impressionistically!’1 Indeed, it was Smart’s immediate experience of the world that provided the visual subject matter for his paintings, his attention often caught by an ordinary, passing glance: ‘suddenly I will see something that seizes me – a shape, a combination of shapes, a play of light or shadows, and I send up a prayer because I know I have seen a picture.’2 Night stop, Bombay, 1981, one of Smart’s most potent and dramatic images, came from one such intriguing view – sketched from the gangway of an aeroplane in the early hours of the morning during one of the artist’s many international trips.

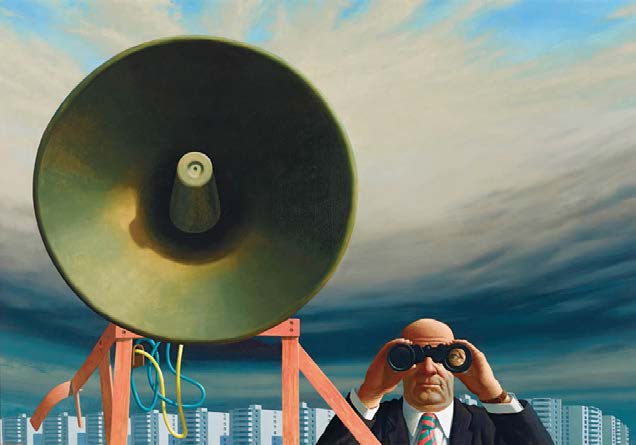

Coinciding with a period of settled comfort with his partner Ermes de Zan in their Tuscan home ‘Posticcia Nuova’, from the late 1970s Jeffrey Smart’s art increasingly explored the notions of real and metaphorical travel. In addition to his permanent expatriation in Italy, Smart was an inveterate traveller. In 1980, he visited the United Kingdom, Egypt and Turkey before being called back to Australia in March 1981 following the death of his mother. On his return to Italy, he made stopovers to visit Hittite cities in Turkey, Syria and Yemen.3 He was particularly attuned to the cultural predicament of Australia’s remoteness, relying heavily on increasingly affordable air travel to maintain a presence with Australian audiences. Perhaps due to these frequent departures, Smart’s artistic output for 1981 was somewhat limited, only producing three final paintings: The ball game, Athens (private collection); Night stop, Bombay and The ventilators, the Domain (private collection). Seductive in its crisp ‘super realism’ and formal restraint, Night stop, Bombay is Smart at his finest, displaying strong iconographic affinities with some of his most celebrated works, including the iconic The guiding spheres II (Homage to Cézanne), 1979 – 80 (private collection) and The observer II, 1983 – 84 (private collection).

2.jpg

Like a freeze frame of a film, the closely cropped images of Smart’s world are loaded with a sense of intrigue, the suggestion of action existing and persisting just beyond the viewer’s line of sight. Seen from above, Night stop, Bombay presents a bird’s eye view of the tarmac of an airport runway, the larger context of air travel only obliquely referenced. Captured within the target of a yellow circle painted onto the asphalt, Smart paints a worker in bright orange overalls talking on the phone with a looping cable, his back turned to the viewer. Lovingly painted, a massive, disembodied wheel dominates the composition. The dramatic chiaroscuro of light flooding just one corner of the square canvas endows this view with a dream-like vividness. Discarded behind the worker lies a pair of hand-held lollipop markers, with distinctive blue-and-white striped handles – the arcane choreography of air marshalling long having been abandoned. In Night stop, Bombay, Smart clearly delights in the interplay of circles and directional lines, distilling them through the spatial and geometric relationships between the painted road marking, the discarded objects and the giant wheel. The vertiginous view down onto the painted tarmac from the height of an aircraft, disorientingly removes the horizon from view. This device was laboriously refined by Smart many years before in another airport painting of a solitary figure, Madrid airport, 1965 – 66 (private collection). Similar to the tarmac in Madrid airport, which is conspicuously grimy, bearing the traces of the machinery of mass transport, here in Bombay, the yellow road marking is splotched with grease, as Smart noted within his rapid in-situ sketch.

3.jpg

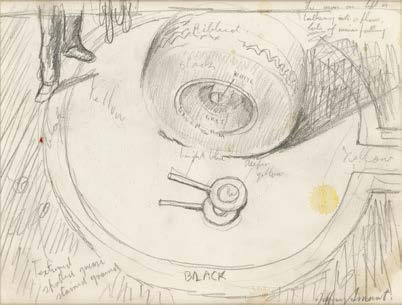

The initial sketch, offered alongside Night stop, Bombay, reveals the rapid crystallisation of the motif, ‘becoming, more or less, without much alteration, the finished work’.4 Annotated with colour notes and areas of interest requiring greater detail, and a single splotch of yellow watercolour in the centre of the circle, the full composition is almost entirely present in this first sketch. The only slight revisions developed in the final painting were in the placement of the wheel, the direction of the sole straight line painted on the tarmac, and the expansion of the figure from just a pair of legs to a full body. Jeffrey Smart also created two detail drawings for Night stop, Bombay. Both addressed the aircraft wheel, on which Smart lavished special, hyper realistic attention, creating from it a visual synecdoche for air travel.

The patterned tread of the rubber tyre, provided for Smart, ‘an interesting decorative element’, justifying his meticulous level of detail. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Smart later revealed his substitution of a truck wheel, a more available form with which he had already become conversant.5 By isolating this distressingly familiar symbol of modern activity, Smart endows it with an elevated, iconic status – its revolving functionality permanently stilled in his silent world.

4.jpg

The airport, more so than the train station or the autostrade beloved of Smart, implies the alienating speed of modern technological progress. The French anthropologist Marc Augé described them, alongside supermarkets and hotels, as ‘non-places of super modernity’, marked by an absence of identity.6 In these liminal environments, people are reduced to logistical points of data to be transmitted and processed. Smart chooses, with characteristic detachment, to present a cropped and oblique view of this transitional space. Creating thus a distinct sense of middle-of-the-night loneliness, Smart’s spotlit view describes a scene of one-way communication and invisible transmission of information. An anonymous airport worker converses with persons unknown, presumably with consequences that will be felt by these inert passengers awaiting transfer to their ultimate destination. Although the large, square canvas of Night stop, Bombay doesn’t adopt the form of an aeroplane porthole, Smart nevertheless gives us a vicarious, through-the-windscreen, view. This privileged view is one only accessible and observable to those pre-approved travellers in transit. While the uniform appearance of an airport conspicuously smooths out cultural differences, Smart’s titles such as Madras airport, 1979; Night stop, Bombay, 1981 and The terrace, Madrid airport, 1984 – 85 all suggest specific points of departure, layover and arrival.

5.jpg

In reducing the vast scale of an airport to that of a single man, Smart zooms in on a small pictorial incident, concentrated in the pool of light in the top left-hand corner of the canvas. Through a sophisticated interplay of surfaces and diagonals of light and shadow, Smart skilfully draws the eye to the startlingly white phone handset and to the mysterious communication with the outside world that it implies. Despite Smart’s suggestion of narrative tension, contemporary writers and commentators on his artworks, Peter Quartermaine and David Malouf, both emphasise a purely formal interpretation of the artist’s paintings. Recalling the hypnotic circular forms of The guiding spheres, 1979 – 80, Smart’s painted yellow road marking in Night stop, Bombay creates a second frame within the square support. In the in-between space of consciousness suspended between time zones and regulated circadian rhythms, it acts as a gleaming ‘mandala for meditation.’7 Smart’s dedicated adherence to the teachings of French modern painting, particularly those of Paul Cézanne, predisposed him to highlight the geometric underpinnings of his paintings. The dominance of clear circular motifs in works from the 1980s, such as Night stop, Bombay and The observer point to Smart’s familiarity with Cézanne’s famous letter to Emile Bernard of 15 April 1904, in which he advised ‘to see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, putting everything into proper perspective, so that each side of an object or plane is directed towards a central point.’8

Smart’s early interactions in Adelaide with the pioneering Modernist Dorrit Black introduced him in the 1940s to the use of an underlying abstract framework on which to arrange a pictorial construction. By the time new modes of non-objective abstract art were emerging from New York in the late 1960s, particularly Hard-Edge and Colour Field painting, Smart had already been painting with an emphasis on geometric forms, saturated colours and flat surfaces for many years. The planar recession of a road’s surface, animated by fragmented symbols, provided Smart with a signature motif. In Night stop, Bombay, the horizon is completely absent, the two-dimensional surface of the tarmac fills the composition, its taut painted contours echoing the essential shapes of contemporary avant-garde abstraction.

6.jpg

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra,

2021 – 22

Reaching their fullest dramatic expression, the paintings emerging from Smart’s halcyon days of the late 1970s and early 1980s became some of his most well-known images. David Malouf wrote of the masterful orchestration of these recent works in 1982 – ‘stripped now of the last suggestion of anecdote or occasion these lyrical and formally dramatic set pieces raise classic questions, which Smart takes up with a seriousness and sense of play that is the real key to their individual mood [...] and joy in the world of his own making of an artist at the top of his form.’9

1. Smart, J., ‘Artists on their art’, Art International, vol. XII/55, 15 May 1968, p. 47

2. Jeffrey Smart, cited in Hawley, J., ‘Jeffrey Smart made simple’, Good Weekend, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 May 1989

3. Hart, D., and Edwards, R., Jeffrey Smart, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2021, p. 148

4. Jeffrey Smart, cited in Quartermaine, P., Jeffrey Smart, Gryphon Books, Melbourne, 1983, p. 92

5. Jeffrey Smart, cited in Capon, E., Jeffrey Smart Drawings and Studies 1942 – 2001, Australian Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2001, p. 109

6. Auge, G., Non-Places: Introduction to an anthropology of super modernity, Verso, London/ New York, 1995

7. Quartermaine, op. cit., p. 94

8. Translation from John Renald, Paul Cézanne, London, 1950, p. 172, cited in Quartermaine, op. cit., p. 120

9. Malouf, D., ‘Jeffrey Smart - Recent Works’, Art International, vol. XXV, no. 9, 1982, p. 69

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH