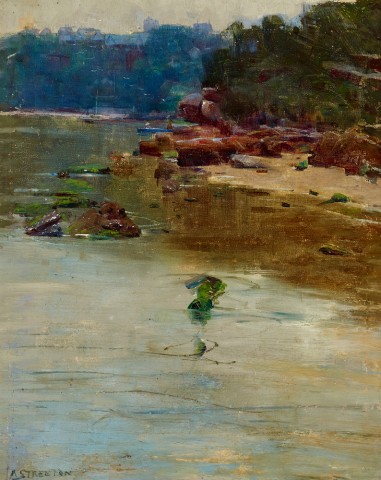

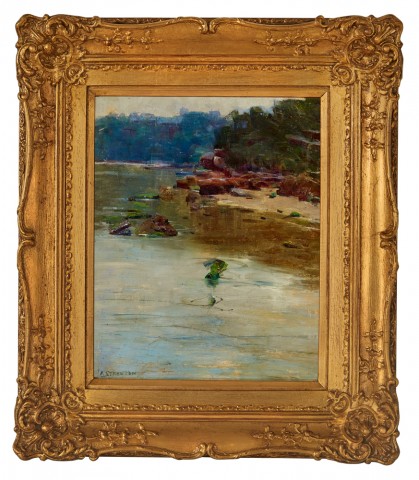

SIRIUS COVE, SYDNEY, c.1893 - 95

ARTHUR STREETON

oil on canvas

36.0 x 28.5 cm

signed lower left: A STREETON

Private collection, Sydney [frame by S.A. Parker]

Private collection, Adelaide, acquired prior to 1968

Thence by descent

Private collection, Adelaide

Sir Arthur Streeton Exhibition, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 6 - 23 March 1968, cat. 71 (label attached verso, as ‘Sydney Harbour, 1908’)

Exhibition of Past Australian Painters Lent From Private South Australian Collections, Adelaide Festival of Arts, John Martin & Co. Limited, Adelaide, 8 – 29 March 1974, cat. 108 (label attached verso, as ‘Sirius Cove’)

111.jpg

‘And then it dipped again, more and more steeply, a shadowy woodland path by this time, showing sudden wide views of the intense blue waters, all overspread with the twinkling dazzle of the reflected sun; and at last it dipped down to the shore, a quiet, lonely, sheltered shore, with a narrow strip of white beach on which little wavelets broke and bubbled, faintly echoing the sound and fury of the ocean surf outside. And here was the camp – a cluster of tents, a little garden, a woodstack, a water tub – almost hidden in the trees and bushes … the camp looked out upon the great gateway of the Heads, and saw all the ships that passed through, voyaging to the distant world and back again. But the ships did not see it.’1

This evocative description of a Sydney harbourside camp featured in Ada Cambridge’s novel, A Marked Man, which was serialised in the Melbourne Age newspaper between 1888 – 89. Arthur Streeton may well have read it there, but by this time, Charles Conder had painted at the camp it describes and his friend and fellow artist, Tom Roberts, had probably visited during a recent trip to Sydney.2 Streeton and Roberts sailed for Sydney together in late 1891, lured by the promise of a rich prize for watercolour landscapes offered by the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, as well as its more enlightened attitude towards collecting Australian art. Committing some of its annual budget to the work of local artists, the Sydney gallery had recently purchased Streeton’s painting, ‘Still glides the stream, and shall forever glide’, 1890.

Although Sydney didn’t suffer from the effects of the economic Depression as badly as its southern neighbour at this time, there were numerous established campsites on the shores of the harbour. Set up in the 1880s as places for weekend recreation, an escape from the ‘foetid air and gritty of the dusty, dirty city’,3 in the following decade they became permanent dwellings for men who couldn’t afford accommodation in town.4 It was at Curlew Camp, located on the eastern shore of Little Sirius Cove – one of numerous bays along the Mosman peninsula on Sydney’s North Shore – where Roberts and Streeton took up residence. Along with the neighbouring Great Sirius Cove, it was named after the flagship of the First Fleet, HMS Sirius, which was careened there in 1789. Part of the traditional lands of the Cammeraigal and Borogeal peoples, it had long been known as Gorma Bullagong.

Arthur_Streeton_-_From_my_camp_(Sirius_Cove) 210838.jpg

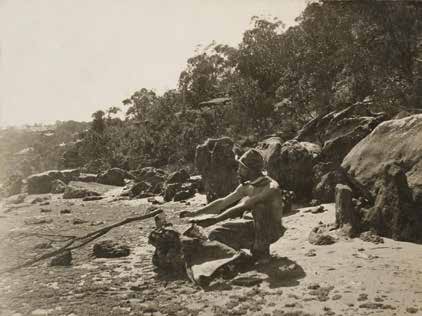

Accommodation was in canvas tents and a contemporary photograph of the communal artists’ tent shows paper lanterns and lengths of fabric draped from the ceiling, cane and bentwood furniture, ornamental floor rugs, plants and a piano – very much the bohemian gathering place.5 With a freshwater creek nearby, the camp also boasted a cook and an odd-jobs man, and evidently suited Roberts and Streeton well. They lived there, on and off, until April 1896 and January 1897 respectively. Curlew Camp was also home to a varied cast of people during these years, including the artists Julian Ashton, A. J. Daplyn and Arthur Henry Fullwood.6 A photograph taken around 1892-93 by Rodney Cherry (a fellow camp resident) of a shirtless Streeton, crouched on the rocky beach at Sirius Cove painting an oil sketch, gives an indication of the simplicity and solitude of camp life. Streeton’s letter to Theodore Fink, written during the summer of 1896, confirms this impression: ‘…Saturday 9pm in our tent at Mossman’s Bay – the front of our tent thrown open wide, & the night sky is deep green blue, & below the great hill the bay reaches down into a deep wonderfull [sic.] gulf, under the sea – picnic parties pulling about quietly through the rare phosphorescence, steamers puffing, breathing heavily & fluting away, & all with me is melody.’7 He wasn’t completely removed from the city however, and as funds allowed, maintained a studio there which was easily accessible via the Mosman ferry which docked beyond the point a short walk from camp.

Streeton was entranced by the ocean, describing it in a letter to Roberts as, ‘a big wonder … a great miracle’, which was ‘hard to comprehend … like death & sleep.’8 It was a central focus of many paintings made during the first half of the 1890s, such as Near Streeton’s Camp at Sirius Cove, 1892 (New England Regional Art Museum) and From my Camp (Sirius Cove), 1896 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) – typically coloured vivid ‘Streeton blue’, sparkling and reflecting the clear blue skies above. In other examples, such as Sirius Cove, c.1895 (National Gallery of Australia) and the current painting, Sirius Cove, Sydney, c.1893-95, the colour is more subdued, as Streeton conveys the sometimes moody atmosphere of the area he had observed so closely and knew so well. In this view, Streeton shares an intimate view of his landscape, looking out across the tranquil waters from Whiting Beach – where Curlew Camp was located – towards Cremorne Point in the distance. The dusky silhouettes of houses and tall buildings lining the horizon remind us that the suburbs and the city are not far away, but it is the peaceful, secluded beach flanked by bush which prevails. The distinctive rocky outcrop of Little Sirius Point in the middle distance leads on to Great Sirius Cove, where a sail boat sits beneath a band of white birds flying above and two figures rowing in a small boat near the shore.In 1900, The Bulletin claimed that it was Streeton, rather than Captain Arthur Phillip, who had discovered Sydney Harbour.9 His myriad paintings of the subject, even then, well-known and loved, had already become iconic depictions of what Mark Twain, upon visiting in 1895, described as ‘the darling of Sydney and the wonder of the world … beautiful – superbly beautiful’.10 Streeton’s singular vision of the harbour and surrounding landscape captured its light, movement and colour, eschewing the realism of other depictions,11 and conveying its distinctive atmosphere in a manner that makes these images as appealing today as they were at the time they were painted.

1. Cambridge, A., A Marked Man, Sydney, 1987, chap. 24, p. 163 quoted in Eagle, M., ‘Streeton in the City of Laughing Loveliness’, Lane, T., Australian Impressionism, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2007, p. 201. First published in London in 1891, this was serialised in the Age between 1888-89 under the title, The Black Sheep.

2. Eagle, ibid.

3. Thomas, A., Bohemians in the Bush: The Artists’ Camps of Mosman, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1991, p. 31

4. See Topliss, H., The Artists’ Camps: Plein Air Painting in Australia, Hedley Australia Publications, Melbourne, 1992, p. 134; Thomas, ibid.; and Eagle, M., The Oil Paintings of Arthur Streeton in the NGA, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1994, p. 61

5. Topliss, ibid., p. 135

6. Eagle, 1994, op. cit.

7. Streeton to Theodore Fink, c. January 1896, quoted in Galbally, A. and Gray, A., Letters from Smike: The Letters of Arthur Streeton 1890-1943, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989, p. 66

8. Streeton to Tom Roberts, quoted in Eagle, 2007, op. cit., p. 207

9. See Mimmocchi, D., ‘An Artist’s City: Streeton in Sydney’ in Tunnicliffe, W., Streeton, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2020, p. 96

10. Twain, M., Following the Equator: A Journey around the World, Hartford, Connecticut, 1897, chap. 9, p. 57 quoted in Eagle, 2007, op. cit., p. 204

11. Eagle, ibid.

KIRSTY GRANT