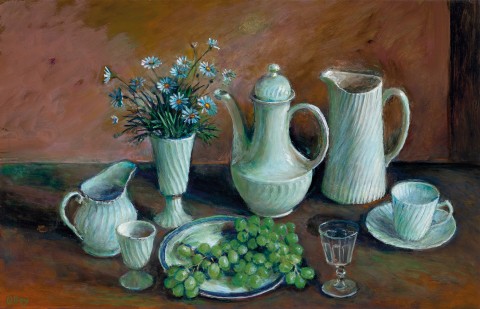

UNTITLED (STILL LIFE WITH DAISIES AND GRAPES), 1979

MARGARET OLLEY

oil on composition board

53.5 x 83.5 cm

signed lower left: Olley

Eva Breuer Art Dealer, Sydney, 2005 (label attached verso)

Private collection, Canberra

Menzies, Sydney, 11 May 2017, lot 36

Private collection, Melbourne

The Olley Project, [https://ehive.com/collections/5439/objects/498395/white-still-life-with-... (accessed 26/10/22)

‘…I can think of no other painter of the present time who orchestrates his or her themes with such richness as Margaret Olley. She is a symphonist among flower painters; a painter who calls upon the full resources of the modern palette to express her joy in the beauty of things.’1

A much-loved, vibrant personality of the Australian art world for over 60 years, Margaret Olley exerted an enduring influence not only as a remarkably talented artist, but as a nurturing mentor, inspirational muse and generous philanthropist. Awarded an Order of Australia in 1991 and a Companion of the Order of Australia in 2006, Olley featured as the subject of two Archibald-Prize winning portraits (the first by William Dobell in 1948, and the second by contemporary artist Ben Quilty in 2011, just prior to her death) and was honoured with over 90 solo exhibitions during her lifetime, including a major retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1997. Today her work is held in all major state and regional galleries in Australia, and the myriad contents of her Paddington studio have been immortalised in a permanent installation at the Tweed Regional Gallery in northern New South Wales, not far from where Olley was born. Bequeathing a legacy as bountiful as the subject matter of her paintings, indeed her achievements are difficult to overstate – and reach far beyond the irrepressible sense of joy her art still brings.

A striking example of the still-life scenes for which Olley remains widely celebrated, Untitled (Still Life with Daisies and Grapes), 1979 encapsulates well the way in which she repeatedly turned to the quotidian for inspiration, excavating her domestic setting to uncover the beauty inherent in everyday life. Featuring a celadon green tea set juxtaposed against an earth-coloured background to accentuate its curved patterning and enlivened by the inclusion of fresh grapes and blue daisies to inject colour and life, significantly the composition belongs to a decade in Olley’s career that was defined by an increased experimentation with the spatial and chromatic possibilities of her art. For, notwithstanding the apparent randomness of her arrangements, fundamental to such compositions was her masterful ‘curation’ of elements to create a harmonious, perfectly balanced image – an aesthetic directly inspired by her firsthand experience of the theatre in 1948 when she assisted with painting the sets for Sam Hughes’ productions of Shakespeare’s Pericles and Cocteau’s Orphée (designed by Jean Bellette and Sidney Nolan respectively). Observing the actors being instructed to enter the stage and count twenty seconds before speaking their lines, the young artist soon came to appreciate the importance of creating space for oneself; as she fondly recalls, ‘space is the secret of life… it is everything.’2

Paying homage to the great European masters of her métier such as Vermeer, Bonnard, Matisse and Cézanne, thus Olley meticulously orchestrates the various components of her exquisite still lifes as if characters on a stage – objects both commonplace and beautiful, shuffled this way and that, plunged into deep shadow or transformed by lighting. Leading the viewer’s eye and mind through an intimate, deeply personal drama that resonates with the artist’s delight in her domestic surrounds, each composition reveals the very essence of her identity; as Barry Pearce elucidates, ‘…to live with a Margaret Olley painting is to experience the transfiguration of a passionate, highly focused personality into art. In her paintings, the space surrounding each bowl of fruit, each vase of flowers, and through which the eye traverses a cacophony of surfaces such as patterned carpets, modulated walls, and cluttered tabletops, resounds with her presence. These are reflections of the things she loves, and which embellished the centre of how she prefers her existence to be.’3

1. Gleeson, J., ‘Introduction’, Margaret Olley, The Johnstone Gallery, Brisbane, 1964, n.p.

2. Margaret Olley cited in Pearce, B., Margaret Olley, The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1996, p. 14

3. Pearce, B., ‘Margaret Olley Retrospective’, State of the Arts, Sydney, August – November 1996, p.5

VERONICA ANGELATOS