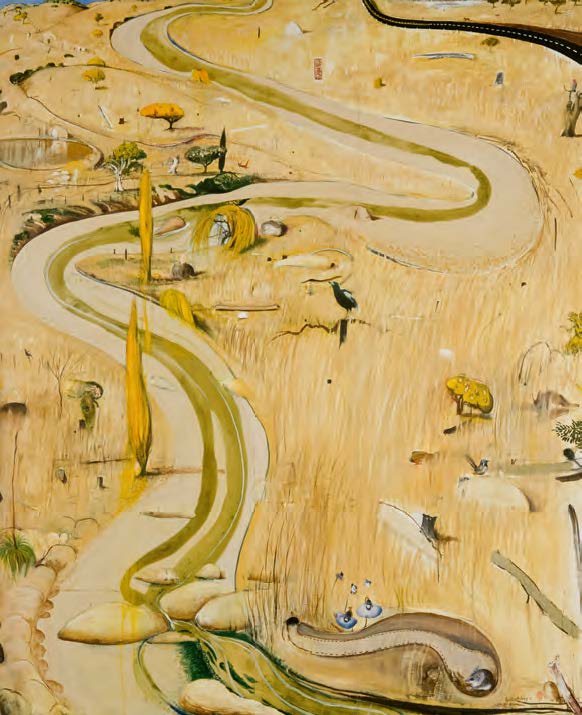

THE WREN, 1978

BRETT WHITELEY

oil on canvas

168.0 x 153.0 cm

signed lower right: brett whiteley

Australian Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in July 1978

Brett Whiteley: paintings, drawings and three scrolls plus one bronze from 1960 Italy never before shown in Australia, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 12 – 25 July 1978, cat. 48 (label attached verso)

Makin, J., ‘Which Brett is for real?’, The Sun, Melbourne, 19 July 1978, p. 32

Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné, Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, cat. 243.78, vol. 3, p. 556 (illus.), vol. 7, p. 457

(Blue Wren), c.1979, mixed media and collage on card, 101.5 x 76.0 cm, private collection, illus. in Sutherland, K., in Sutherland, K., op. cit., cat. 176.79, vol. 3, p. 636

ARC262.1.96##M.jpg

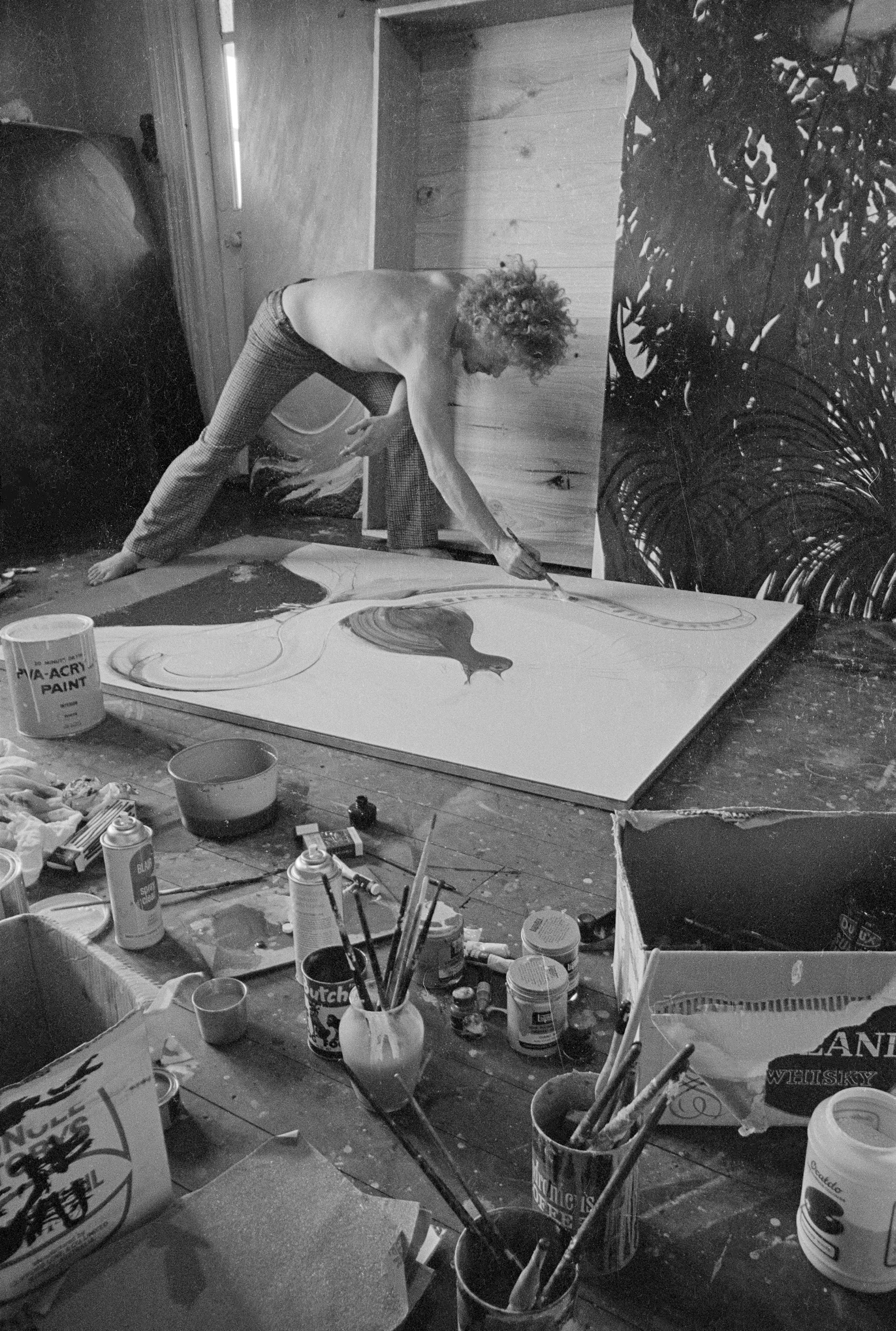

Brett Whiteley in his studio, 1970

photographer: Robert Walker

© Robert Walker/Copyright Agency, 2024

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

‘Of all the subjects Whiteley painted in his career, landscape gave him the greatest sense of release…’1

After a tumultuous decade abroad, in 1969 Brett Whiteley returned to Australia and, in the tradition of many expatriate artists before him, thus embarked upon an artistic pilgrimage to rediscover his homeland. Captivated afresh by the beauty, vastness and variety of the Australian landscape, he thus explored the shifting chromatic illusions and ‘optical ecstasy’ of Sydney’s Lavender Bay in sumptuous tableaux redolent of Matisse, before subsequently revisiting the country of his boyhood in the central west of New South Wales – returning ‘to the rounded, monumental, full-breasted hills and open spaces that surround Bathurst’.2 Today universally acclaimed among the most relaxed and quietly assured paintings of Whiteley’s career, the resultant landscapes immortalising the central west thus exuded a distinct lightness and easy spontaneity – an intimacy derived from the artist’s deep identification with this region’s geography over the span of three decades. Capturing the shimmering heat that descends on these rolling hills and gentle vales during the blaze of an Australian summer, The Wren, 1978 represents a particularly magnificent example from this celebrated period within Whiteley’s oeuvre – evoking both the detached grandeur of classical Chinese painting, and the close emotional engagement of his spiritual and artistic hero, Vincent Van Gogh. Hailing from that auspicious year when Whiteley was at the very height of his fame – his annus mirabilis of 1978 in which he became the first artist ever to win all three of the country’s most coveted art prizes (namely the Archibald Prize for Portraiture; the Wynne Prize for Landscape and Sulman Prize for Genre) – indeed the work is Whiteley at his finest, elegantly encapsulating his luminous colour, sensual line and characteristic verve all in poignant homage to the landscape where his journey as a painter first began.

* * * * * * * * * *

Whiteley Around Bathurst.jpg

| Brett Whiteley Around Bathurst, 1959 oil and sand on composition board, 122.3 x 143.0 cm Private collection © Wendy Whiteley/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

Lloyd Rees Road to Berry.jpg

| Brett Whiteley On the Road to Berry, 1947 oil on canvas on paperboard, 34.6 x 42.2 cm Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © A&J Rees/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

In February 1948, amidst the demands of managing a business and maintaining their hectic social schedule, Clem and Beryl Whiteley made the steely decision to uproot their children – Brett, aged eight and sister, Frannie, aged ten – and pack them off to boarding schools some three hundred kilometres away from Sydney.3 Seething with frustration at his loss of freedom and the regimentation of boarding life at The Scots School, Bathurst, not surprisingly Whiteley felt banished, rejected and angry; as he later reflected, ‘The days were so long – it was all so stretched out. A term seemed three years. It really was a punishment and there was nothing else to do but to invent my own world – to set up a device to deal with it.’4 Notwithstanding such negatives, there were also triumphs and with hindsight, the Bathurst experience proved crucially important to Whiteley’s future development as a painter – influencing his understanding of the landscape and its seasons in a way that could not have been possible had he remained in Sydney during these formative childhood years. Notably, his teachers were perspicacious and supportive of their reluctant student’s precocious artistic talent, encouraging him to set up an easel at the back of the classroom from which he could paint the view through the window – whether it be ‘a wren that landed on a tree branch’ or ‘the hills, the sort of caressed breasts of Bathurst’.5 Moreover, on Sundays during his final years of high school, Whiteley and his close friend, Vernon Treweeke, were granted special permission to leave the school grounds to explore and paint en plein air the surrounding Bathurst countryside – with one composition from such excursions earning Whiteley first prize in the Young Painters section of the 1956 Bathurst Show.6 Significantly, after leaving school and while working at the Lintas advertising agency in the city, Whiteley would continue to make weekend sketching expeditions over the Blue Mountains to Bathurst, Ulladulla, Sofala and Hill End, and notably, it was a central west landscape from this time, Around Bathurst, 1959 (private collection) that won him the Italian Government Travelling Art Scholarship for 1960.7

If these seminal experiences nurtured the beginning of a profound and enduring attachment to the landscape of the New South Wales central west – a connection Whiteley described as ‘a sense of feeling close to the earth’8 – his response was also inevitably conditioned by a boundless admiration for that great visual rhapsodist of the region, Lloyd Rees. As famously recounted, Whiteley first made the serendipitous discovery in 1954 when, as a curious, wide-eyed fifteen year old dressed in his school’s cadet uniform, he wandered into a solo exhibition of Rees’ recently painted landscapes at Macquarie Galleries in Sydney.9 Deeply poetic in their contemplation of soft curves and arabesques all rendered with impeccable tonality, such images instinctively appealed to a young Whiteley in his ‘obsession’ with the sensuality of the landscape – with the child prodigy believing he had found in Rees a kindred artistic spirit. Indeed, Rees’ interpretations of the landscape left such an indelible impression upon his consciousness that decades later Whiteley not only dedicated an entire series to celebrating the master’s creative genius, but would write to his frail mentor to pay tribute: ‘I wanted to convey to you just how important an influence you have been on my life and on my art, how one event in 1954 had a profound effect on my understanding of what painting was and could be, and that the realisation that day has continued to influence and inspire me to this day.’10

352.1998##M_web.jpg

Brett Whiteley

To Yirrawala, 1972

oil and mixed media on board, 185.3 x 166.3 x 6.3 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

© Wendy Whiteley/Copyright Agency, 2024dh140468.jpg

Brett Whiteley

Orange Fruit Dove, Fiji, 1969

oil and mixed media on composition board, 136.5 x 122.0 cm

Private collection

© Wendy Whiteley/Copyright Agency, 2024

Although attracted to the overtly sexual elements he perceived in Rees’ landscape, Whiteley nevertheless doubted that ‘old Reesey’ would have recognised such allusions in his own work.11 Years after the encounter at Macquarie Galleries, Whiteley would repeatedly visit Bathurst and Orange with fellow artist Michael Johnson, ‘hunting for Reesey’s hills’, remarking ‘Look at those rolling contours, he’s modelling the torso…’. As Johnson recalls, ‘We got so excited thinking of the landscape as a female figure, but we’d never say any of this to Lloyd. Lloyd was a nineteenth-century man, settled into what he was, and we were twentieth-century kids, searching for the new.’12 Today one need only consider Whiteley’s early landscapes, such as The Black Sun, Bathurst, 1957 (private collection) – a portrait of melancholia prompted by his mother’s departure for an indefinite period overseas following the breakdown of her marriage to Clem – alongside Rees’ iconic south coast painting, The Road to Berry, 1947 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) to appreciate the master’s defining influence. And in turn, the debt of both artists to the surrealist landscapes of British abstractionist Graham Sutherland – in particular, his Welsh Mountains, 1937, one of the few international modern paintings hanging in the Art Gallery of New South Wales at the time.13 Beyond the sensual abstracted forms of his soulful landscapes moreover, Whiteley also absorbed Rees’ predilection for intentionally leaving visible pentimenti or traces of the artwork’s evolution within the finished composition – a dynamic painterly technique that would become a hallmark of the younger artist’s oeuvre. As Whiteley recalled of his landscapes at the Macquarie Galleries’ exhibition, ‘…they contained naturalism but also seemed very invented, and the adventure of them was that they showed the decisions and revisions that had been made while they had been painted. I had never seen anything like that before… it set me on a path of discovery that I am still on today – namely that change of pace in a painting is where the poetry begins.’14

* * * * * * * * * *

Still reeling from his experience of living the turbulent, not-quite ‘American dream’, it is of little surprise that Whiteley should seek out the landscape of the central west for solace and inspiration upon his return to his homeland. As Barry Pearce, emeritus curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, has noted: ‘…if in many of his other themes Whiteley confronted the difficult questions of his psyche, landscape provided a means of escape, an unencumbered absorption into a painless, floating world.’15 Oscillating between periods of extreme dependence on narcotics and restorative sojourns in the countryside (where the Whiteleys would invariably stay at the home of influential radio host, John Laws, in Oberon, or Michael Hobbs in Carcoar), thus the years that ensued witnessed the production of some of the most beautiful, highly acclaimed landscapes of Whiteley’s career – aptly earning him the epithet of ‘chronologist of the golden paddocks, sensual hills and willow-strewn rivers of the central west.’16 Culminating most famously in his highly successful solo show, ‘Rivers’, held at Robin Gibson Gallery, Sydney in March 1977, as well as the two Wynne-Prize winning paintings – River at Marulan (…Reading Einstein’s Geography), 1976 (private collection) and Summer at Carcoar, 1977 (Newcastle Art Gallery) – such large-scale landscapes poetically captured the region in its myriad moods and seasons, featuring birds, rivers, trees, rocks, skidding insects and shy mammals (both painted and assemblage), all brought together with elegiac majesty.

Monumental in scale and conception, The Wren exemplifies brilliantly this genre – complementing the dominant vertical perspective of the gliding river that ascends the picture plane with an acute attention to detail to exquisitely depict the tough beauty of a drought-ravaged landscape in mid-summer. Indeed, as Jeffrey Makin, art critic for the Sun astutely observed upon the painting’s unveiling at Australian Galleries in 1978, ‘As a performer Whiteley knows few equals. His understanding of the mechanics of composition are [sic] often excellent as evidenced in ‘The Wren’. Here the relationship between flattened space and incident – ie. that bouncy blue bird – is beautifully balanced.’17 Recalling the legacy bequeathed by artistic predecessors Russell Dysdale and Sidney Nolan in their stark portrayal of the country’s parched interior, thus the composition similarly evokes all the colour and drama of drought – presenting a theatre of death and survival in the same reductive palette of pale desiccated yellows punctuated by cobalt blue highlights that Whiteley so favoured in masterworks such as River at Carcoar; To Yirrawalla, 1971 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); and Blue River, 1977 (private collection).

BW.4.jpg

| Brett Whiteley Summer at Carcoar, 1977 oil and mixed media on pineboard, 244.0 x 198.7 cm Newcastle Art Gallery, New South Wales © Wendy Whiteley/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

Yet, as intimated by the painting’s title, it could well be argued that Whiteley’s focus here is as much upon the motif of the little blue wren as it is the expansive landscape. Occupying a poignant place in his iconography from early in his artistic journey, birds embodied for Whiteley not only peace and tranquility – a refuge from the internal demons that haunted him – but in his later work particularly, represented a yearning at once for both domestic stability and personal freedom. As Margot Hilton and Graeme Blundell elaborated, ‘Whiteley so loved birds, loved the way they hung overhead, tacking against the breeze, sliding sideways, wheeling and screeching away. He loved their freedom, the mindless glide of them. They were like a blessing on his life, an indication that the hand of God was at work…’18, they were ‘the essential symbol of the song of creation’19. Whether painted, drawn , collaged or stuffed and mounted, ornithological creatures populate Whiteley’s most important works – from the hummingbird and eagle appearing in his chaotic multipaneled American Dream, 1968 – 69 (Art Gallery of Western Australia) and the lyrebird, blue wren and even Donald Duck nestled within Alchemy, 1972 – 73 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), to his individual portraits dedicated to particular species – for example, Orange Fruit Dove, Fiji, 1969 (private collection, Brisbane); Pink Heron, 1969 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); Lyrebird, 1972 – 73 (private collection, Sydney); Hummingbird and Frangipani, 1986 (private collection) and even a Butcher Bird with Baudelaire’s Eyes, 1972 (private collection, Sydney). And of course, there are the whimsical avian sculptures – a Picasso-esque owl created from a boot; pelicans fashioned from dried palm fronds; and giant egg sculptures atop Brancusian pole-plinths. Bereft of any hint of angst or menace and ‘motivated more by love than despair’20, not surprisingly such bird paintings remain among Whiteley’s most universally admired achievements; in the words of Sydney poet, Robert Gray, ‘In Whiteley’s bird paintings is embodied his finest feeling; they are to me his best work. I like in the bird shapes that clarity; that classical, haptic shapeliness; that calm – those clear, perfect lines of a Chinese vase. The breasts of his birds swell with the most attractive emotion in his work. It is bold, vulnerable and tender.’21

Situated both thematically and chronologically between the two legendary late 1970s solo shows that explored the themes of the Bathurst landscape and birds respectively – namely his 1977 ‘Rivers’ and 1979 ‘Birds and Animals’ exhibitions, both held at Robin Gibson Gallery, Sydney – thus The Wren encapsulates Whiteley at his most lyrical, with his signature sweeping calligraphic line, dominant palette of sun-bleached yellows and luminous blues, and refreshing sense of freedom, optimism and contentment. An arcadian refuge of tranquil release and contemplation that seems almost beyond time in its stillness, indeed the masterpiece betrays an elegance and harmony unmistakably redolent of the Chinese art that Whiteley so admired, with the ‘repetition of motifs symbolising states of mind…the arabesques echoing the flightpaths of birds, which in turn mirrored the artist’s relaxed journey through his own domain.’22 In stark contrast to his more gruelling, visually demanding canvases of previous years, here there is no complex artifice, no anthropomorphic forms, nor flamboyant burlesques. Rather, Whiteley simply offers a romantic celebration of Nature in all her sensuality and rugged beauty, paying tribute to the landscape of his boyhood which first inspired his journey as a painter all those years ago. As the artist himself reflected upon such landscapes at the time, ‘…Sometimes I have to paint pictures that have an effortless naturalness, not artificial or synthetic, not manufactured – pictures that have no affectation through mental tricks but are graceful and according to nature.’23

1. Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley: Art and Life, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1995, p. 196

2. McGrath, S., Brett Whiteley, Bay Books, Victoria, 1979, p. 206

3. Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: A Sensual Line, 1957 – 67, Macmillan, Sydney, 2010, p. 15

4. Brett Whiteley, cited in McGrath, op. cit., p. 18

5. Brett Whiteley in Interview with Phillip Adams, radio 2UE, Sydney, September 1986

6. Sutherland, op. cit.

7. In November 1959, Whiteley was awarded Italian Government Travelling Art Scholarship for 1960, judged by Sir Russell Drysdale at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Whiteley submitted four entries: Sofala; Dixon Street; July c.1959; and Around Bathurst, 1959 the painting that won him the scholarship.

8. Brett Whiteley, cited in McGrath, op. cit., p. 18

9. Lloyd Rees: 22 European Paintings, 17 March 1954, Macquarie Galleries, Sydney.

10. Brett Whiteley, cited in Klepac, L., Lloyd Rees – Brett Whiteley: On the Road to Berry, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993, p. 7

11. According to Wendy, Rees was reportedly astounded when Whiteley pointed out to him the overt sexual elements that he had found in his paintings: see Hawley, J., ‘Whiteley and Rees: An Inspiring Friendship’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 8 July 1992, pp. 13 – 17, cited in Sutherland, op. cit., p. 19

12. Michael Johnson, cited in Hawley, ibid., p. 17

13. Graham Sutherland, Welsh Mountains,1937, oil on canvas, 56.0 x 91.0 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales. For discussion of the influence of this work upon both artists, see Pearce, op. cit., p. 18 and Sutherland, op. cit., p. 19

14. Brett Whiteley, cited in Klepac, op. cit.

15. Pearce, op. cit.

16. Hopkirk, F., Brett Whiteley 1958 – 1989: The Central West, Orange Regional Gallery, Orange, 1990

17. Makin, J., ‘Which Brett is for real?’, The Sun, Melbourne, 19 July 1978, p. 32

18. Hilton, M and Blundell, G., Whiteley: An Unauthorised Life, Macmillan, Sydney, 1996, p. 215

19. Pearce, B., Australian Artists, Australian Birds, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1989, p. 144

20. McCulloch, A., ‘A Letter from Australia’, Art International, October 1970, pp. 69 – 70

21. Gray, R., ‘A Few Takes on Whiteley’, Art and Australia, vol. 24, no. 2, Summer 1986, p. 222

22. Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley: 9 Shades of Whiteley (Education Kit), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, p. 25

23. Brett Whiteley cited in McGrath, op. cit., p. 216

VERONICA ANGELATOS