Banksy: A Collection of Works (lots 54 – 59)

1.jpg

Despite remaining officially anonymous, Banksy has become a household name, and his highly recognisable graphic motifs have reached far beyond the local street art scene from which he emerged in the late 1990s. In 2010, Time magazine compiled a list of the 100 most influential people in the world, including the English street artist, who, having always taken great care to protect his anonymity, appeared masked with a paper bag. Banksy’s messages, in contrast, are stencilled plainly in black-and-white on city walls, editioned in print and virally shared the world over, boldly addressing the unjust truths of contemporary society. Working from the guerrilla underground art scene of Bristol, Banksy’s provocative humanist motifs were first painted directly, or ‘bombed’, in the streets. Fulfilling a democratic and anti-elitist ethos, these murals reached ordinary people on their commutes around the city, and Banksy’s distinctive style of visual metaphor quickly gained broad popular support.

In many cases, Banksy’s images first appeared clandestinely sprayed directly onto street walls at prominent city junctions or emblazoned on cardboard protest signs used in mass public demonstrations throughout the early 2000s. To clearly communicate and appeal to the broadest possible audience, Banksy’s images feature simplified and easily readable archetypes, emblems around which to rally. Contravening the artist’s noble intent of democratic access to art, many of Banksy’s original public artworks have since been removed. His images instead survive in the medium of screen-prints, which were commercially published and distributed in limited print runs by the artist-run cooperative ‘Pictures on Walls’ throughout the early 2000s.

In this medium, Banksy stands on the shoulders of giants, notably Andy Warhol, who was amongst the first to recognise the potential of the silkscreen to preserve the defining images of a generation. Warhol’s experimentations with printmaking set in motion the dismantling of hierarchical boundaries separating art media. In so doing, he also provided a framework for Banksy to reinterpret his site-specific practice into a tool of mass distribution, satisfying the artist’s disdain for the commercial structures of the art world.

2.jpg

Rude Copper, 2002, is considered to be the first of Banksy’s commercial prints, produced with Steve Lazarides, Banksy‘s agent at the time, and published in an edition of 250 examples. Its simple composition presents a British police officer in traditional uniform, his custodian ‘bobby’ helmet partially concealing his face, making an obscene hand gesture. Exemplifying Banksy’s famous anti-authoritarian stance common to practitioners of street art, Rude Copper derides these avatars of government power. It was produced during a time of strong popular criticism of the Terrorism Act, which, in 2000, expanded the Metropolitan Police’s powers to arrest and detain without warrant.

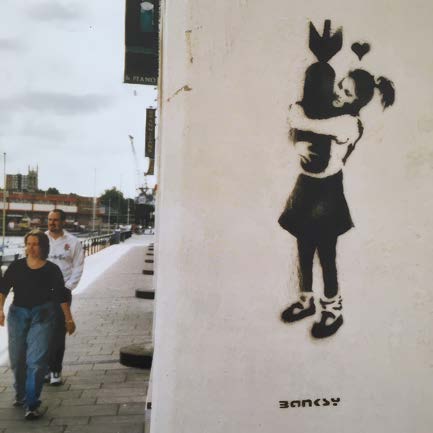

Bomb Love, Laugh Now, and HMV were all early prints in Banksy’s oeuvre, produced the following year, in 2003. One of Banksy’s most powerful anti-war works addressing the controversial Iraq war, Bomb Love, features a little girl cuddling up to a missile, an incongruous contrast of innocence and violence – originally stencilled in East London in 2001 and later screenprinted with a fluorescent pink background. Laugh Now and HMV both use personified animals to make broader commentaries on power. Laugh Now is one of Banksy’s most enduring images: a forlorn monkey wearing a sandwich board transformed into a messenger of an impending revolution, retaliation for the historical and enduring mistreatment of animals in the entertainment industry. Similarly addressing inequalities of the entertainment industry, HMV appropriates the 1921 logo of the British music publishing company His Master’s Voice, giving the dog a bazooka with which to counter the directions of his master transmitted through the gramophone.

Barcode, 2004, transforms the stripes of these ubiquitous machine-readable symbols of commerce into the bent bars of a cage transporting a leopard. Showing the leopard walking free from the strictures of trade and exploitation, Banksy presents a hopeful scene of self-emancipation. Similarly criticising our dependence on mass-market consumerism, Trolleys, 2007, shows a group of prehistoric humans attempting to hunt a trio of shopping trolleys abandoned in their desert plain. With a comic juxtaposition of traditional hunting-and-gathering practices with these icons of contemporary processed and packaged food, Banksy highlights our collective loss of skills and social collaboration.

Taking a rapid and resource-efficient method of creating artwork (aerosol and stencil cut-out) and applying it to an equally rapid mass-distributed medium, Banksy has been able to react and comment on current events almost immediately, creating valuable visual records of the anti-war and anti-establishment zeitgeist of the turn of the millennium.

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH

RETURN TO CATALOGUE