IMPORTANT PAINTINGS BY JIRRAWUN ARTISTS FROM THE HELENE TEICHMANN COLLECTION, LOTS 23 – 29

It is with great pleasure that Deutscher and Hackett offer important paintings by Jirrawun artists from the collection of Helene Teichmann. Helene has a strong connection with Jirrawun Arts, being a former Chairman of the organisation and the works from her collection represents the artists at their prime. Each painting tells a story of the Gija lived experience from the conflict of colonial expansion as shown in the works by Freddie Timms and Peggy Patrick to Phyllis Thomas’ expression of traditional body paint designs and Paddy Bedford’s unique depiction of the Kimberley landscape and history. We are most grateful to Quentin Sprague for his fine introductory essay Looking Forward Looking Back based on a longer composition he wrote in the Bathurst Regional Gallery exhibition catalogue of the same name, an exhibition where the majority of the paintings were exhibited.

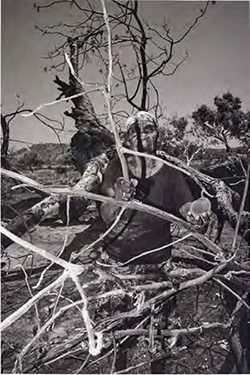

How to describe broken landscapes

The most widely circulated story of Jirrawun Arts – the unique Aboriginal-owned organisation that operated in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia for a decade from 1998 – frames it as a shining example of the Gija notion of Two-Way.

Two-Way is a simple idea: it refers to the bringing together of two previously separate worlds. The artists who worked with the ex-Melbourne gallerist Tony Oliver to form Jirrawun – key among them Freddie Timms, Paddy Bedford, Peggy Patrick, Phyllis Thomas, Rusty Peters, Goody Barrett and Rammey Ramsey – surely understood this well. They were born before the introduction of equal wages brought to an end the broadscale Aboriginal participation in the northern pastoral industry: theirs was a time when working between worlds was the way of Kimberley life; not an option, but a necessity.

But as specific as it is, Two-Way carries a wider resonance. In the case of Australia – a nation that remains heavily weighted by its colonial inheritance – the phrase evokes the bringing together of settler-Australian, or settler-colonial, ways, with Aboriginal ways. The notion is not strictly Gija in formation. One hears it widely, the kind of ideal it expresses has often manifested in Australia as two worlds with largely antagonistic histories try to find a means to move forward as one.

DH2020 Aboriginal Catologue MARCH FA2.jpg

Often such ideals are symbolic in form, more aspiration than actuality. In 2017, for example, this was captured on a national scale by the Yolngu Matha word Makarrata: an idea not dissimilar to Two-Way that was attached to the political ideals that drew together around the Uluru Statement From The Heart, and the attendant debate around constitutional recognition for First Nations people. Described as a ‘complex’ word, Makarrata refers to a tribal mediation between warring parties: a coming together after the storm of conflict. Like Two-Way, the fashion in which it crystalises something longed-for yet held largely out of reach grants it a certain alluring appeal. It’s easy to think that it offers something ameliorative, that it lays history at rest, that it forgives.

But such concepts are often layered with meanings: they can be read in more than one way. As Merrikiyawuy Ganambarr-Stubbs, a Yolngu woman of the Gumatj clan and principal of the Yirrkala school in northeast Arnhem Land, explained in 2018 to the ABC, Makarrata at one level speaks of a spear penetrating the thigh of a wrongful party: tribal punishment in its barest form. This is done, Ganambarr-Stubbs said, ‘so that they cannot hunt any more, that they cannot walk properly, that they cannot run properly; to maim them, to settle them down, to calm them – that’s Makarrata.’

No surprise, perhaps, that in a political context where symbolism too often trumps meaningful action, the word’s more general meaning was the one taken to heart: peace after a dispute; a negotiation after which each party looks upon the other with no bad feeling. Although rooted in another part of Aboriginal Australia, Two-Way can be seen in similar terms: a symbolic ideal that nonetheless speaks of the more direct sacrifices that working between cultures truly demands. It can be taken at face value, but it might equally be seen as a challenge as much as anything, a laying down of the gauntlet that asks what it would take for the broken landscapes left in the wake of colonisation to once again become places of vitality and health.

Among the Gija people who first championed the concept of Two-Way was the late Hector Jandany. In the early 1980s he helped establish a school in the East Kimberley community of Warmun, putting in place a series of lessons that bookended for children a day’s lessons.

Painting formed part of this: Jandany was among those who used the medium as a key teaching tool at a time that artists in the community were working towards the invention of what would become known as East Kimberley art, the movement most closely associated with its initial figurehead, Rover Thomas. Like them, Jandany would transcribe his iconic images onto whatever was at hand: a sheet of cardboard, perhaps, or a plywood off-cut. When the teaching was done, these images would be hung in the classroom: evidence, one imagines, of an ideal striving for actual form.

Years later, when Jandany met Tony Oliver, who had travelled to the Kimberley at the invitation of the late artist Freddie Timms, he imparted the same lesson. Oliver and Timms were intent on creating a new kind of bush art studio, soon to become Jirrawun Arts, and Jandany had a simple instruction: the enterprise had to be underpinned by the notion he held dear: Two-Way had to lie at its heart.

Under Oliver’s stewardship, Jirrawun Arts took this idea and ran with it. Over a decade that traced the most pronounced period of Australia’s market-driven fascination with Aboriginal art, the organisation and its artists went from strength to strength. The works that constitute the collection presented here represent the organisation’s high watermark: they were made in the years where the vision that underwrote Jirrawun came as close as it ever would to some kind of fulfillment. For this reason, Two-Way threads its way through these paintings like a kind of mantra. It’s not simply that they reach out for some kind of resolution to difficult histories (although a number of them do exactly this), but more that they speak a language of exchange that we are yet to fully comprehend. Take, for example, Peggy Patrick’s Mistake Creek, 2004, a work that draws forth its energies not just from the story of the Mistake Creek massacre, in which Patrick’s own family were killed, but from the graphic sensibilities of Pop Art’s fey master, Andy Warhol.

This is a different kind of coming-together, but it’s equally as charged. At one level, it’s simply evidence of how Oliver himself helped shape the Jirrawun vision. As a young art dealer he had been an enthusiastic advocate of American art, and had in Melbourne staged exhibitions by figures as celebrated as Warhol and Philip Guston. What resulted in the Kimberley was a kind of doubling between artistic traditions: Gija painting on the one hand, and the currents of American modernism and Pop Art on the other. This is perhaps most evident in the simple fact of scale and intensity that came to mark much of the work associated with the Jirrawun artists. These are qualities that have always lain latent in Aboriginal art – from its earliest days it presented a core difference wrapped in the familiarity of the painted medium – but the work presented here reaches further. It reminds us that in the artists of Jirrawun Oliver found a reciprocal willingness to take him in, to use their knowledge to shape his. The works that resulted seemed often to argue that the simple function of art was to answer the very question Two-Way first strived to articulate: how might the space between two previously irreconcilable worlds be bridged?

Yet if these paintings do provide an answer, it is far from an easy one. If we are to understand it in the fashion proposed above, Two-Way carries with it a challenge for white Australia. It is often romanticised, as if the phrase alone creates the outcome it seeks, yet little attention is given to how difficult it is to reach that mix of consensus, respect and compromise that actively working between cultures demands. Little attention is given to that fact that in Australia such ideals often falter and fade: that they often leave dashed hopes in their aftermath. In this, they become a measure of how far we, as a nation, have to go.

DH2020 Aboriginal Catologue MARCH FA3.jpg

The idea that art might somehow reconcile the colonial inheritance of a nation is, of course, as admirable as it is impossible. Surely Jirrawun, as both a group of artists and as an organisation, knew this. That’s why the paintings, even as they might be called ‘beautiful’ without a second thought, are also so hard, so evocative of the violence that carried settlers into the Kimberley. It’s why an artist like Paddy Bedford became synonymous not just with paintings of country, but with the story of the Bedford Downs massacre: an act perpetrated by Paddy Quilty, the same white man who gave Bedford his gardiya name. Such contrasts betray the patterns of the frontier, the way it continues to underscore so clearly the interactions that play out between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in this country. It’s for this reason that these paintings show aspects of two worlds vying for common ground: a space staged here as the symbolic space of the painted canvas, but which elsewhere might be understood as a political space, or elsewhere again a legal one, even one of revolutionary promise.

As we look at these paintings more than a decade since they were first made, they urge a more complicated understanding of Two-Way. Two separate ways can perhaps never become one without true sacrifice. Perhaps this is the lesson that the artists of Jirrawun sought to impart: without the wrongful party being ritually maimed, without that party being forced to settle, to be calmed, to be halted from hunting with impunity on Aboriginal land, Two-Way is nothing at all.

QUENTIN SPRAGUE

RETURN TO CATALOGUE