Important Works by Lin Onus from the collection of S&P Global, Australia

Lin Onus

Extraordinarily beautiful and technically flawless, the paintings of Lin Onus (1948 – 1996) exhibit a complex mixture of ideas set around place, ownership and history wherein they occupy a distinctive position in the broader setting of Australian art. Paintings such as those offered here from the Collection of S&P Global, Australia have the capacity to transfix the viewer and are full of meaning, what Michael O’Farrell observed as ‘the sheer tactility of Lin Onus… imagery that establishes a carefully balanced dialogue of sensory and mental elements.’1 Renowned for incorporating satire and humour in his early political installations and paintings that challenged cultural hegemonies, it is in these later paintings that Onus demonstrated his Indigenous connection to country. Poetic landscapes of the natural world, combined with subtle traditional iconography, confirmed Onus’ relationship to both his adopted homeland in Arnhem Land and to his own ancestral sites at the Barmah-forest on the Murray River.

Growing up in a culturally productive and politically engaged household in Melbourne, Lin Onus could not help but be influenced by the activism of his family. His mother Mary Kelly was of Scottish origin and an active member of the Australian communist party, and his father Bill Onus, a Yorta Yorta man from the Aboriginal mission of Cummerangunja near Echuca, was an important figure in the Aboriginal civil rights movement, whose Aboriginal Enterprises (1952 – 68) provided an outlet for Aboriginal art and craft in defiance of the then national goal of assimilation. In 1957 Bill Onus, together with Doug Nicholls, established the Aboriginal Advancement League in Victoria with a goal to ‘promote cultural renewal and reawaken aboriginal pride.’2 Onus’ cultural education on his Aboriginal side was provided by visits to Cummerangunja with his father, and stories told by his uncle Aaron Briggs, who gave him his Koori name – Burrinja, meaning 'star’.3 They would sit on the banks of the Murray River within view of the Barmah Forest – Onus’ spiritual home and the subject of many of his paintings. Leaving school at 14, Lin Onus began his largely self-taught artistic career assisting his father in decorating artefacts. After embarking on a panel-beating apprenticeship, he developed skills working on metal and painting with an airbrush. By 1974, he was painting watercolours and photorealist landscapes and in 1975, he held his first exhibition and began a set of paintings based on Musqito, the first Aboriginal guerrilla fighter, which still hang on the walls of the Advancement League in Melbourne.

While overtones of bullying and racism experienced by Onus in 1960s suburban Melbourne influenced much of his art, the cultural revelations that came from his friendship with respected painter Jack Wunuwun (1930 – 1991), enabled Onus to embrace both his indigenous and non-indigenous heritage. Having first met Wunuwun at Maningrida in 1986 while travelling in his role as the Victorian representative for the Aboriginal Arts Board, his life from that moment was deeply influenced by this encounter with the late Yolngu elder and artist, who adopted Onus as his own son.

Over the next decade, Onus made sixteen ‘spiritual pilgrimages’ to the outstation of Garmedi, the home of Jack Wunuwun in Central Arnhem land.4 Wunuwun was able to offer Onus a kind of cultural sanctuary by welcoming him into the Yolngu kinship system. This relationship provided Onus with the opportunity to learn Aboriginal traditional knowledge, which enhanced his own Yorta Yorta experience of the world. Through Wunuwun, Onus was given creation stories that he was permitted to paint and an Aboriginal language he could also access. As Onus noted ‘going to Arnhem Land gave him back all the stuff that colonialism had taken away – Language and Ceremony.’5 Onus acquired his knowledge of symbols, patterns and designs from the community elders, and it seemed to him that this experience of tradition was ‘like a missing piece’ of a puzzle which ‘clicked into position’ for him culturally.6 The resulting personal style juxtaposed the rarrk clan patterns of Maningrida, learnt from the older artist, with a photorealist style of landscape, integrating Indigenous spirituality and narrative with Western representation.

The two major paintings consigned from the Collection of S&P Global, Australia, Malwan Pond – Dawn, 1994 and Goonya Ga Girrarng (Fish and Leaves), 1995 were acquired from Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi in Melbourne. Both present photorealist images of central Arnhem Land wetlands, where the surrounding tall trees are reflected in the cool dark water of the billabong and fish glide just below the surface of the water, affording glimpses of the traditional markings that cover their bodies. Leaves float on the surface and or sink to the bottom, becoming detritus on the floor of the billabong.

Reflections are essential to the art of Lin Onus, literally and metaphorically. Both his painting and his social activism address issues of identity, racism and the uneven power relationship between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Onus held a mirror to unresolved social inequality within this country and explored what it meant to be Australian, while his luminous paintings reflect a desire to create an art that could be appreciated on numerous levels by everyone. His series of watery landscapes of the Arafura Swamp or Barmah Forest which, rich in reflections and ambiguities, substituted the traditional European panoramic view for one of cross-cultural imagery, thus subverting the primacy of Western modes of representation.

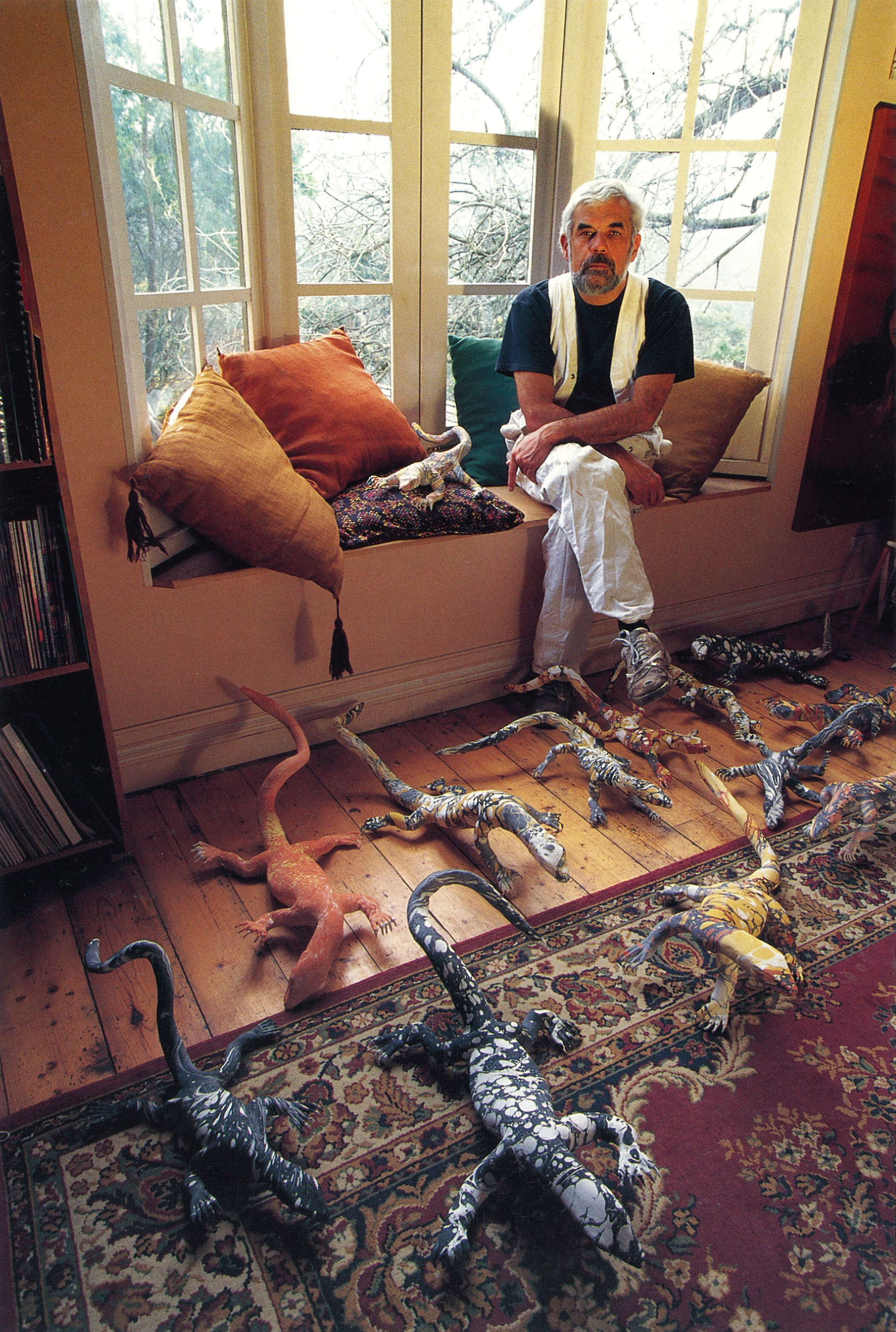

Six gouache works painted on card also offered here follow a similar structure. Picturesque landscapes contain indigenised creatures that present a duality described by Robert Nelson as a ‘form of symbolic realism’ – noting Onus’ ability to use both the traditional idiom of perceptual art in the landscape tradition, together with fish, frogs and reptiles painted according to Aboriginal conventions.7 Here his gouaches of indigenised frogs, lizards, butterflies and bats set in Australian landscapes become part of the process of reclaiming custodianship of the land and its inhabitants, thus fulfilling a sense of belonging.

Lin Onus hoped that ‘history would see him as some sort of bridge between cultures’8 and as articulated by Ian Mclean, ‘[he] successfully used postmodern strategies to infiltrate issues of Aboriginality into everyday Australian life.’9 Unifying different cultures, languages and visual perspectives, his distinct and celebrated work reflects both his activism and creative ambitions, with his activism finding its greatest voice through his prodigious talent for painting and his ability to stop people in their tracks with his beautiful yet powerful image making. A self-taught artist living between cultures and communities, Onus found a way to bring together Indigenous and non-indigenous understandings of landscape and in a spirit of reconciliation, to articulate the intersection of two sets of values and points of view.

1. O’Ferrall, M., ‘Lin Onus’ in Australian Perspecta 1991, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1991 p. 80

2. Kleinert, S., ‘Aboriginal Enterprises: negotiating an urban Aboriginality’, Aboriginal History, vol. 34, 2010, see https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p170581/html/ch07.xhtml?referer=1272&page=8, accessed online September 2022

3. Neale, M., Urban Dingo: The Art of Lin Onus 1948–1996, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2000, p. 14

4. Ibid., p. 15

5. Ibid.

6. Leslie, D., ‘Coming home to the land’, Eureka Street, March – April 2006, https://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article/coming-home-to-the-land, accessed September 2022

7. Neale, op. cit., 2000, p. 16

8. Ibid., p. 21

9. Ibid., p. 41

CRISPIN GUTTERIDGE

BACK TO CATALOGUE