“Of perhaps even more value for anthropology than the descriptions of Aboriginal life by Péron, Baudin and others are the drawings by Petit and Lesueur… The engravers did not idealize the originals as much as their predecessors had but, even so, for the freshness and acuteness shown by Petit and Lesueur, one must look at the originals, or photographic reproductions of them.”

Frank Horner, The French Reconnaissance, p. 367.

NOTE:

The standard reference to the collections of the Muséum d’historie naturelle at Le Havre is Baudin in Australian Waters by Jacqueline Bonnemains, Elliott Forsyth and Bernard Smith. It is frequently cited in the catalogue that follows, referred to by the abbreviation BAW. The reference numbers used by Jacqueline Bonnemains in the same work to identify artworks in the collection of the Muséum are given in the form B:12345.

INTRODUCTION

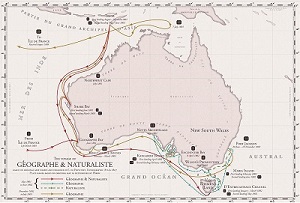

This catalogue, researched and prepared by Hordern House describes a substantial collection of Baudin voyage art. Most such collections of voyage art found permanent homes in the nineteenth century, and have remained basically static since, meaning that it is startling to have something genuinely new, and perhaps revolutionary, to add to this critically important story.

All of the works in the present catalogue are by the two main artists on the voyage, Nicolas-Martin Petit and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, and all of them until very recently formed part of a remarkable collection of voyage art from a single French collection, having been in the vendor’s family since the mid-nineteenth century. Prior to their recent rediscovery and sale in Paris, all of the works were completely unknown and unrecorded.

This is one of only two major caches of Petit and Lesueur works which both date from the voyage and which later became part of the core group of images considered for publication in the official account: the first cache is, of course, now part of the collection of the Le Havre Muséum d’histoire naturelle, acquired in the late 1870s and since recognised as the centrepiece of the visual history of the voyage. Even taking into account the Le Havre collection, only a relatively small catalogue of known Baudin voyage works by either Petit or Lesueur survives, and they are extraordinarily rare on the open market, especially as concerns Australian subjects.

In terms of the present catalogue, Petit’s ability most obviously shines through in the Tasmanian portraits in gouache, which transcend simple voyage art. But the way the eye is drawn to them should not detract from the other riches, his two original sketches of Tasmanian men, as well as the two Timorese and two Sydney works from his pen, along with his fascinating images of competing groups. Petit’s artistic skill no doubt reflects, in part, his studies with the most celebrated French artist of the day, the great neo-classicist, Jacques-Louis David.

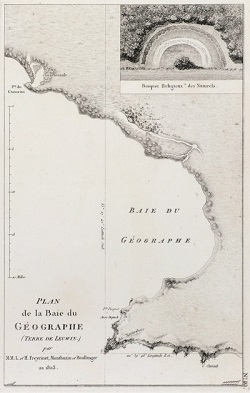

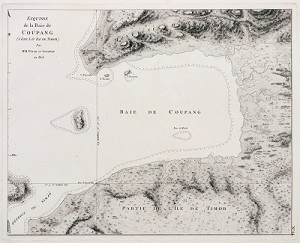

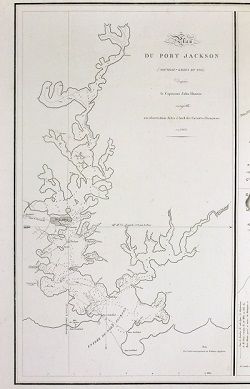

By the same token, although now chiefly remembered as a scientist and natural history artist, the three views by Lesueur, depicting Timor, a scene on the Vasse in Western Australia and a view in Port Jackson, are major additions to his oeuvre, and extremely rare examples of any of his Baudin voyage artworks. As we describe in detail in this publication, each of these Lesueur views is of singular importance, none more so than the extremely early Western Australian scene.

That the present group of works exists at all is testament to the care with which they were preserved by a series of voyage veterans and custodians: Petit and Lesueur themselves, but also François Péron and Louis de Freycinet, all of whom took possession of this group over a forty-year period marked by official indifference and political turbulence. All of these works are in remarkable condition, having been in the care of individuals –either directly involved in the Baudin voyage or later, as this publication documents, a French family with naval connections – who recognised their unique artistic and historical significance. The gouaches in particular are striking in terms of their clarity and strength of colour.

Hordern House in association with Deutscher and Hackett are delighted to havethe opportunity to offer this collection, and hope that the present catalogue will both honour and more fully describe these most important works of art relating to early Australia.

THE COLLECTION

The works of both Petit and Lesueur on the Baudin voyage have been much studied, most significantly in the ground-breaking “Baudin in Australian Waters” (BAW). As that work and the many studies and exhibitions that have followed show, the other known portraits by Petit, the great majority of which are held by Le Havre, are famous as much for their beauty as their mystery, chiefly because although they later became the basis for the eye-catching engravings in the published atlas of views (1807), very little was written by any of the French officers or scientists describing their interactions. Crucially, no notebook or journal by Petit himself has ever been recorded, which may explain why the scenes of Aboriginal life dominate the visual record, but are under-described in Péron’s accompanying text.

The most likely reason for this disparity between the visual and written records is that in the original planning for the voyage publication there was supposed to be a complete extra volume on the ethnography of the people of Timor, Tasmania and mainland Australia. Péron himself, who had some training in the nascent field of anthropology, was to be the author of this work: that a magisterial work was planned is clear, but so is the fact that no part of it was ever published, and that only fragments of it now remain, of which none are more vital than the pictures themselves.

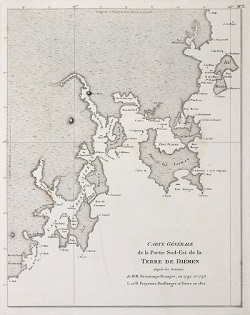

In this publication each of the individual works is illustrated and described, where it is clear that while the group includes an embarrassment of riches, that primus inter pares are the Tasmanian portraits by Petit, blazing comets in the known history of the Baudin voyage. All of these Tasmanian portraits were created in early 1802 as a record of the series of interviews the French had with the men and women of D’Entrecasteaux Channel.

As we discuss the import of these Tasmanian pictures, the central point is that following the work of John Webber on Cook’s third voyage (amounting to a handful of original sketches and the associated engraved plates), and the known works of Jean Piron on the D’Entrecasteaux voyage (some simple pencil outline sketches in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, and four engraved plates in the account published by La Billardière), the portraits of Petit are the last pre-settlement works.

As a result, the rediscovery of these five unrecorded Tasmanian portraits, three evocative works in gouache, and two of the on-the-spot drawings done by Petit ashore, is quite astounding. We strongly believe that at least four of the portraits will prove to have been done during the Baudin expedition’s stay in the region of North West Bay at the northern end of D’Entrecasteaux Channel, between 19 January and 5 February 1802: if true, they will be the only works known to have been done by Petit on mainland Tasmania.

Not only that, but a remarkable eyewitness report survives that confirms the Tasmanian portraits must have been done on board the Géographe and before the meeting with Flinders at Encounter Bay: no less a figure than Robert Brown, the botanist serving with Flinders, was hastily called upon to act as a translator when Baudin and Flinders met in 1802, and immediately after the meeting he dashed off a memorandum recording his impressions (now held at the British Museum, Natural History Department). Brown wrote:

“C Baudin showd us coloured figures of the natives of Van Diemens land they appeared to be characteristic but not well executed. There were figures of their huts, of their tombs, & of their canoes. The canoe is exactly similar to that given by Billardière. All of the natives were painted with woolly hair & C Baudin on being questiond on this head assurd us that it was really so. The hair of all the figures was of an ochry red in all probability from the ochre with which they colour their whole bodies…”1

The idea of Baudin and Flinders looking through these portraits as they rested at Encounter Bay is a striking and quite moving thought.

Brown’s eye may not have been ready to appreciate what he saw, but it is not his opinion that concerns us. What matters now is that he is explicit that the portraits that Baudin and Flinders examined together were coloured: the only extant coloured portraits that Petit is recorded as having made in Tasmania were the series of gouaches and now a single work in pastel (also in the present catalogue).

Even reduced to simple numbers the importance of these works is apparent. In the great review of the Baudin voyage by Bonnemains, Forsyth and Smith (BAW) only eleven gouaches of Tasmanian subjects are listed, making the addition of three more a cause for celebration, the more so because, as is described in more detail in this publication, each of the three is unusually well-provided with notes and details that make it possible to reimagine this entire period.

1. R.W. Giblin, Flinders, Baudin, and Brown at Encounter Bay, pp. 4-5

Return to Top