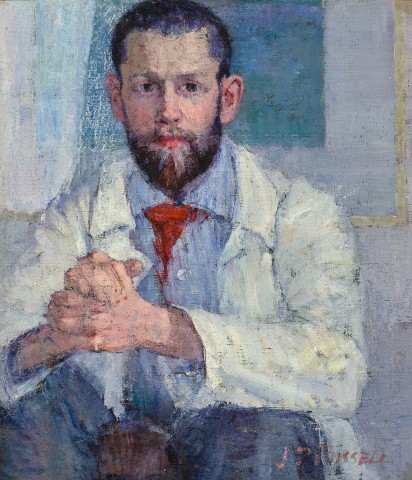

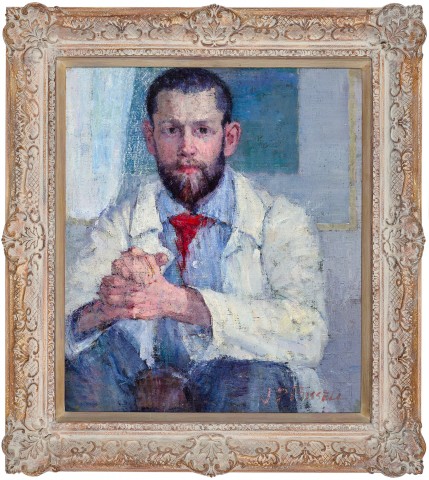

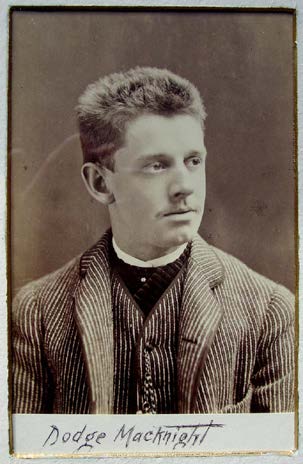

Portrait of Dodge Macknight, c.1888

John Peter russell

oil on canvas

55.5 x 47.5 cm

signed lower right: JP RUSSELL

Bequeathed by Dodge Macknight to his sister-in-law, Elise Queyrel, Massachusetts, USA

Thence by descent

Mrs George W. Bruce, Massachusetts, USA

Thence by descent

Private collection, Delaware, USA

Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, 29 August 2007, lot 48

Private collection, Melbourne

An Impressionist in Sandwich: The Paintings of Dodge Macknight, Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, Massachusetts, 15 November - 21 December 1980, cat. 68 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, p. 4)

Australian Impressionists in France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 15 June – 6 October 2013 (label attached verso)

John Peter Russell: Australia's French Impressionist, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 21 July – 11 November 2018 (label attached verso)

Letter from Vincent van Gogh to John Peter Russell, Arles, 19 April 1888 (collection of The Guggenheim Museum, New York) https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let598/letter.html

Salter, E., The Lost Impressionist: a biography of John Peter Russell, Angus and Robertson, London, 1976, pp. 75, 95

Galbally, A., The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977, p. 34

Pickvance, R., Van Gogh in Arles, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1984, p. 253

Bailey, M., 'A Friend of Van Gogh, Dodge Macknight and the Post-Impressionists', Apollo Magazine, London, July 2007, pl. 4 (illus.), pp. 30, 31 (illus.)

Fish, P., 'Spring bidding budding', The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 25 August 2007

Jansen, L (ed.) et. al., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 2009, vol. 4, p. 60 (illus.)

Taylor, E., Australian Impressionists in France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013, frontispiece (illus.), pp. 56, 57 (illus.)

Tunnicliffe, W. (ed.), John Peter Russell: Australia's French Impressionist, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2018, pp. 39, 41 (illus., dated 1887 - 88), 203

1.jpg

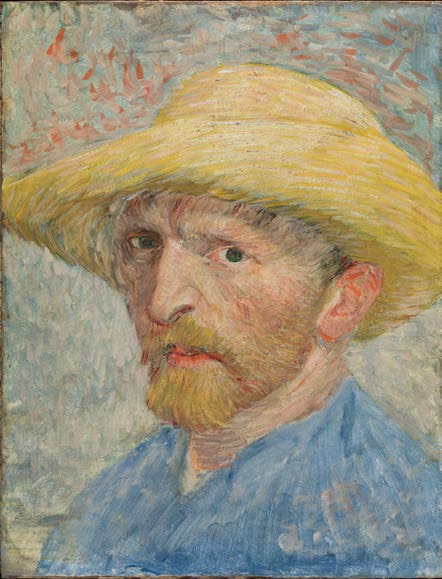

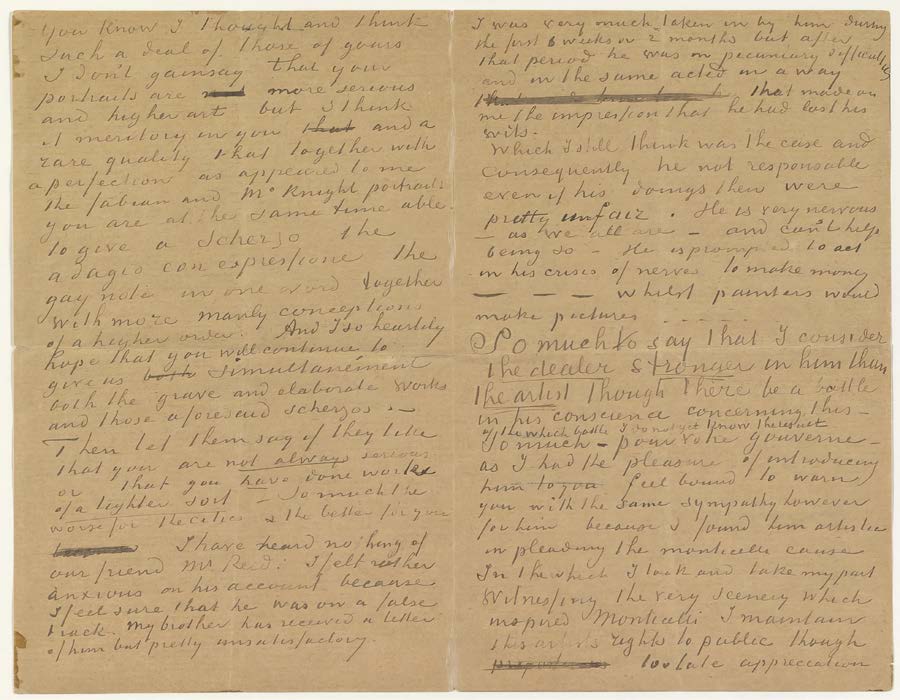

When one of the greatest exponents of modern painting, Dutch master Vincent van Gogh, wrote admiringly of John Peter Russell’s portraits as ‘more serious and higher art’, praising in particular ‘such perfection as appeared to me in the Fabian and Macknight portraits’1, he articulated a keen appreciation for the work of Australia’s ‘lost impressionist’ that continues to resonate more than a century later. Occupying an esteemed position within Russell’s oeuvre, indeed the present Portrait of Dodge Macknight, c.1888 not only encapsulates superbly the artist’s technical brilliance and emotional breadth but, as the only known portrait of the American post-impressionist, the painting bears invaluable historical significance as well. With its whereabouts unknown until 2007, the work’s recent rediscovery has been a particularly exciting one for art critics and collectors alike; as acknowledged by the late Ursula Prunster, curator of the major Belle-Île exhibition held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2001 which featured the work of Russell, Monet, and Matisse, ‘I have been looking for this painting for a while...’2

2.jpg

Although not as widely appreciated today, during his lifetime Dodge Macknight was highly regarded by his contemporaries as America’s first modernist and certainly, one of the world’s four greatest watercolourists.3 Discussing his legacy, a critic for The New Bedford Standard suggested, ‘In contemplating an exhibit of Macknight’s work, one should bear in mind that he is an extremist in an extreme school. His work should not be judged merely in the light of one’s own taste, but as an exposition of the artist’s conceptions. Some people call his paintings mere daubs of colour, others designate them as recorded thoughts transmitted through the eyes.’4

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Macknight began his career in the art world as an apprentice to a theatrical scene designer before entering the firm of Taber Art in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a company that manufactured reproductions of paintings and photographs. In December 1883, at the age of 23, he migrated to Paris where he enrolled at the studio of academic painter Fernand Cormon, studying alongside Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard and Louis Anquetin, together with the two artists who would play a key role in introducing Macknight to the Parisian avant-garde, Eugène Boch and John Peter Russell.

3.jpg

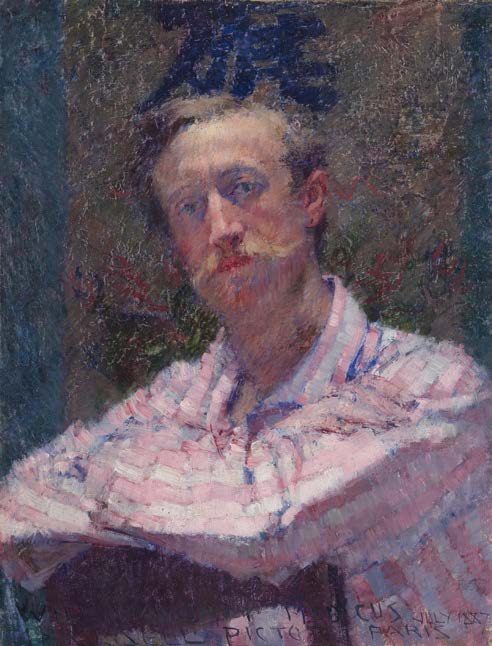

As Martin Bailey elucidates, Macknight and van Gogh first met through Russell in March 1886, the month that van Gogh joined Cormon’s studio, having arrived in Paris from Antwerp on 28 February 1886. Shortly thereafter, Macknight left Paris, heading first for the south of France and later that year for the Algerian coast, while van Gogh remained in Paris for another two years, during which he frequently met with Russell.5 Connected through their mutual status as outsiders in an intensely competitive Parisian art scene, Russell and van Gogh soon forged a close friendship – one that would endure through well-documented letters and exchanges of artwork right up until the latter’s tragic death in 1890. And indeed, it was most probably during these Paris years that the Dutchman posed for his celebrated portrait by Russell which, now housed in the van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, he clearly cherished; as he would subsequently write to his brother Theo in one of his final letters, ‘Take good care of my portrait by Russell which I hold so dear.’6

4.jpg

On 20 February 1888, van Gogh arrived in Arles and several weeks later, Macknight came to Provence, staying in the nearby village of Fontvielle, north-east of Arles.7 Writing to his friend Eugène Boch, Macknight noted that he had ‘unearthed a couple of artists at Arles – a Dane [Christian Mourier-Petersen]’ and Vincent whom I had already met at Russell’s – a stark, staring crank, but a good fellow.’8 Van Gogh too would recount the meeting in a subsequent letter to Russell: ‘Last Sunday, I have met Macknight and a Danish painter, and I intend to go to see him at Fontvielle next Monday. I feel sure I shall prefer him as an artist to what he is as an art critic, his views as such being so narrow they make me smile.’9 And again, in his correspondence with Theo, ‘I must go and see him and his work, of which I have seen nothing so far. He is a Yankee, and probably paints better than most Yankees do. But a Yankee all the same. Is that saying enough? When I’ve seen his paintings or drawings I’ll concede about the work. But about the man, still the same...’10 Ironically perhaps, van Gogh's brusque assessment reflects more of his own notoriously volatile personality than any real dissatisfaction with Macknight, for only days later he would mention to his brother that he had invited the American to move into the Yellow House in Arles: ‘…it’s not impossible that he may come to stay with me here for a while. Then we would benefit, I think, on both sides.’11

5.jpg

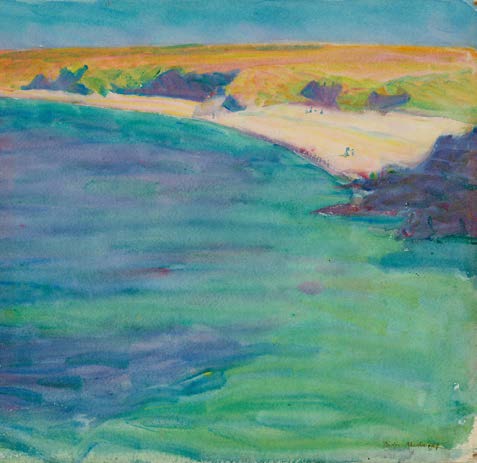

Upon sighting Macknight’s work for the first time, van Gogh was typically gruff, recalling to Theo that ‘…He’s at the stage when the new colour theories are tormenting him, and while they prevent him from doing things according to the old system, he hasn’t sufficiently mastered his new palette to be able to succeed this way.’12 Yet, despite his criticism, the Dutchman was obviously impressed for less than one month later, after having seen various still-lifes that Macknight had just finished featuring ‘a yellow jug on purple foreground, red jug on green, orange jug on blue’13, he executed one of his famous Sunflower canvases with orange flowers in a yellow pot, set against a turquoise background.14 Thus, contrary to the popular assumption of van Gogh as an artistic recluse in Arles, it would seem rather, that he and Macknight were exploring in tandem the theory of disparate colour complementaries.15

6.jpg

At the same time, working with Monet on the remote, storm-tossed island of Belle-Île off the coast of Brittany, interestingly Russell was embracing very similar techniques; as he elucidates in a letter to Heidelberg school artist Tom Roberts back in Melbourne: ‘…No vehicle colour only on absorbed canvas or better on stiff canvas prepared only with glue. Simple colours but strong keep pure as long as possible.’16 Thus, in stark contrast to the darker tonalities of Russell’s 1886 portrait of van Gogh, the present offers a luminous demonstration of the French impressionist technique with the brushstrokes open and relaxed, and the coarse texture weave of the canvas soaking up the paint upon application to reveal the artist’s hand visibly at work. Cropped asymmetrically in a manner reminiscent of Japanese woodcut prints, the vivid white, red and blue-purple palette – shading through a toned white, pink and grey – is at once arresting and harmonious, contributing to create a portrait of great sensitivity and beauty. Closely related to Russell’s highly acclaimed Portrait of Dr Will Maloney 1887 (National Gallery of Victoria) executed around the same time, the portrait moreover betrays that powerful quality of immediacy and informality so essential to the vision of the European avant-garde.

Following in the footsteps of Russell and Monet, in November 1888 Macknight made the first of many visits to Belle-Ile where, pursuing a passion for colour shared and encouraged by the Australian, he would produce some of the finest watercolours of his career. In 1892, he married the governess of Russell's children, Louise Queyrel, and in 1897 the couple and their young son returned to the United States, settling in East Sandwich where Macknight would remain for the rest of his life. Although initially condemned as ‘grotesque and uncouth’17 – barbs not unfamiliar to impressionist artists internationally at that time – his work was soon eagerly sought-after and acquired by public and private collectors alike, including eminent art patron Isabella Stewart Gardner, who had a dedicated ‘Macknight Room’ in her house at Fenway (now the Gardner Museum) and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts which purchased its first watercolour by Macknight in 1907 (five years before the first Sargent acquisition).

7.jpg

with reference to Russell’s Portrait of Dodge Macknight.

Returning to America with Macknight and subsequently passed down through the artist’s family before its first appearance on the market in 2007, thus the present work not only offers a rare glimpse into one of the most fascinating yet often forgotten members of impressionism, but notably, is accompanied by an impeccable provenance. In addition to its historical significance, Portrait of Dodge Macknight also embodies the radical avant-garde theories and experiments which, gleaned by Russell through his personal connection with the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, so distinguish him from the local movement pioneered by the Heidelberg school. As celebrated French sculptor Auguste Rodin astutely prophesised of Russell’s artistic legacy, ‘Your works will live on, I am certain. One day you will be placed on the same level as our friends Monet, Renoir and Van Gogh.’18

1. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to John Peter Russell, Arles, 19 April 1888, letter 598, at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let598/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

2. Ursula Prunster, in conversation with Deutscher and Hackett art specialists (August 2007)

3. Hind, C. L., Art and I, The Bodley Head, New York, 1921, pp. 98, 100 – 101 & 176. The other three were Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent and Hercules Brabazon.

4. The New Bedford Standard, January 1902, cited in An Impressionist in Sandwich: The Paintings of Dodge Macknight, Trustees of the Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, Massachusetts, 1980, p. 6

5. Bailey, M., ‘A Friend of Van Gogh: Dodge Macknight and the Post-Impressionists’, Apollo, July 2007, p. 30

6. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, 5 and 6 September 1889, letter 800, at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let800/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

7. Bailey, op. cit.

8. Dodge Macknight, Letter to Eugène Boch, Fontvielle, 19 April 1888

9. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to John Peter Russell, 19 April 1888, op. cit.

10. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, c.25 April 1888, letter 601, at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let601/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

11. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, c.4 May 1888, letter 603 at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let603/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

12. ibid.

13. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, 29 July 1888, letter 650 at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let650/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

14. Bailey, op. cit., p. 32

15. ibid.

16. John Peter Russell, Letter to Tom Roberts, Paris, 26 December 1887, reproduced in Galbally, A., The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977, p. 90

17. An Impressionist in Sandwich, op. cit., p. 6

18. Auguste Rodin , Letter to John Peter Russell, cited in ‘The Art of John Peter Russell’, Women’s Weekly, 3 May 1967, p. 34 at https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/4832171 (accessed October 2025)

VERONICA ANGELATOS