Watercolours by Albert Namatjira, Lots 28 – 32

Albert namatjira essay image.jpeg

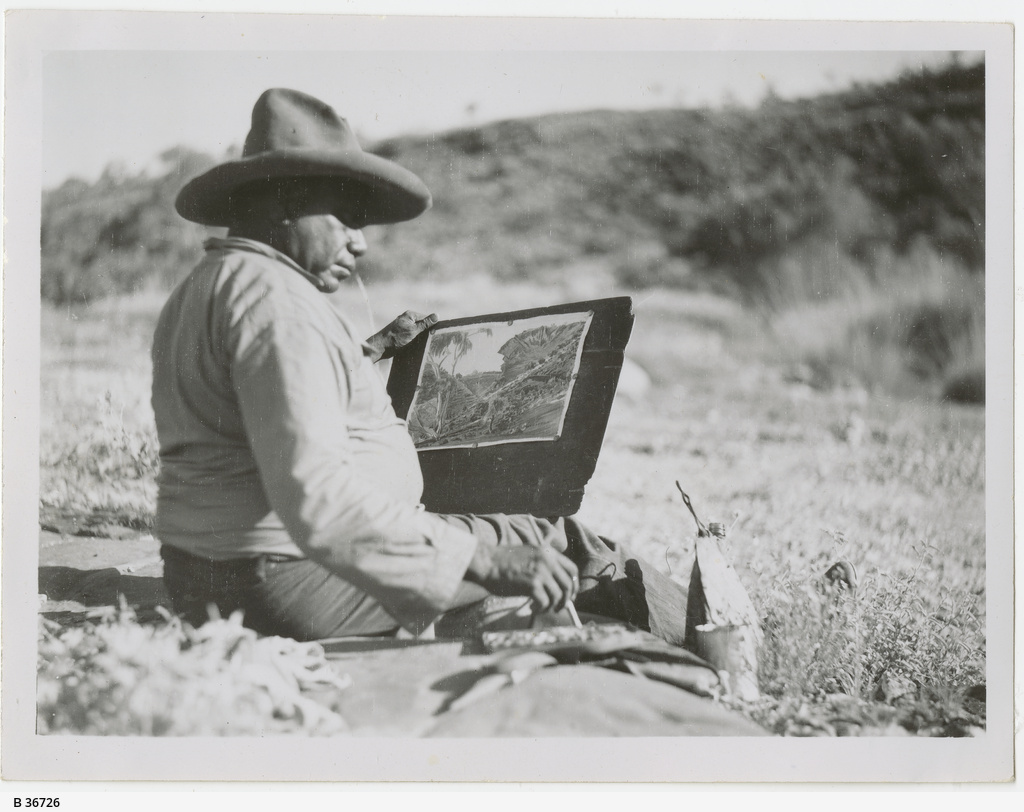

‘…Many years ago, an Aboriginal man from central Australia, Albert Namatjira, became very famous as a painter. Using Western watercolour techniques he painted many landscapes. But what non-aboriginal people didn’t understand, or chose not to understand, was that he was painting his country, the land of the Arrernte people. He was demonstrating to the rest of the world the living title held by his people to the lands they had been on for thousands of years.’1

Although an accomplished craftsman producing poker work decorated woomeras, boomerangs and wooden plaques, it was not until viewing an exhibition of watercolours by Victorian artists Rex Battarbee and John Gardner at the Hermannsburg Mission in 1934, that Albert Namatjira truly embarked upon painting as a profession. Immediately captivated by the medium, he pleaded to be taught watercolour techniques and eventually Battarbee agreed to Namatjira accompanying him on two month-long expeditions in 1936 through the Palm Valley and MacDonnell Range areas. And thus began the cultural exchange that was to become a defining feature of their long relationship; Battarbee instructing Namatjira about the Western technique of watercolour painting, and in turn, Namatjira imparting his sacred knowledge about the subjects they were to paint, namely the land of the Western Arrente people, his ‘Dreaming’ place. So impressive was Namatjira’s skill that Battarbee remarked after only a brief period, ‘I felt he had done so well that he had no more to learn from me about colour’.2 Success and recognition soon followed and Namatjira was launched into the spotlight as a cultural ‘icon’ – internationally acclaimed and admired for his innovative, vibrantly coloured desert landscapes that encouraged ‘new ways of seeing the Centre.’

If today it is synonymous with our vision of the Australian outback, Namatjira’s art nevertheless suffered various vicissitudes over the course of the last century. Although his first solo exhibition in 1938 at the Fine Arts Society in Melbourne was a sell-out success, with popularity and fame continuing throughout his lifetime, praise for Namatjira’s skilful adaptation of a Western medium was inevitably accompanied by a bitter twist; his paintings ‘…were appreciated because of their aesthetic appeal, but they were at the same time a curiosity and sign that Aborigines could be civilised’.3 Ironically such perceived ‘assimilation’ would later bring his art into disrepute with Namatjira virtually ignored by the Australian art establishment during the 1960s and 70s. Fortunately, the Papunya Tula Aboriginal art ‘renaissance’ and cultural politics of reconciliation during the 80s prompted long overdue reassessment of Namatjira’s unique contribution, and more recently, he has received the recognition he so deserves with three biographies published, and three major exhibitions mounted by public galleries, including a retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia in 2002 to celebrate the centenary of his birth, Seeing the Centre: The Art of Albert Namatjira 1902 – 1959.

Capturing the landscape west of Alice Springs – and specifically, his favoured western Arrernte sites of the MacDonnell Ranges (Tjoritja), Simpson’s Gap (Rungutirpa) and Jay Creek – indeed the following five lots offer superb examples of Namatjira’s achievements in their brilliantly-coloured palette and distinctive, Western-style topographical format. Beyond their striking aesthetic appeal however, such works also resonate with important personal symbolism as statements of belonging – coded expressions embodying the memory and sacred knowledge of a traditional ancestral site, Namatjira’s ‘dreaming’ or totem place. As such, they encapsulate the unique vision that has subsequently inspired generations of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike across Australia – ‘Albert’s Gift’ which was more far-reaching than simply the tangible legacy of his art, ‘…more than the sum parts of watercolour paints on paper.’ As Belinda Croft elucidates, ‘It is an essence that resides in the strength of Namatjira’s work – his courage, his sorrow, his spirituality – in these days of ‘reconciliation’, but most of all, in the spiritual heritage of every indigenous person in Australia.’4

1. Galarrwuy Yunupingu cited in ‘The black/white conflict’ in Caruana, W. (ed.), Windows on the Dreaming, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, Ellsyd Press, Sydney, 1989, p. 14

2. Morphy, H., Aboriginal Art, Phaidon Press, London, 1998, p. 268

3. Ibid., p. 270

4. Croft, B., ‘Albert’s Gift’ in French, A., Seeing the Centre: The Art of Albert Namatjira 1902 – 1959, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2002, p. 148

VERONICA ANGELATOS