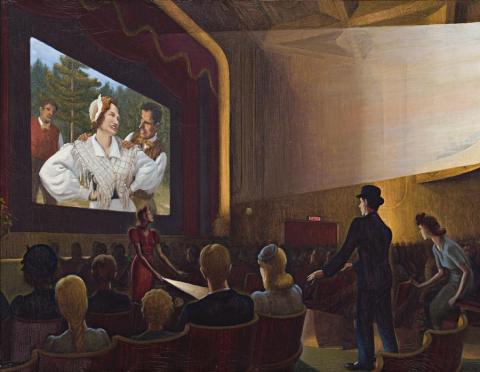

TECHNICOLOUR, c.1944

Weaver Hawkins

oil on canvas

71.0 x 91.5 cm

signed verso: H. WEAVER HAWKINS

Private collection, Sydney

Deutscher Fine Art, Melbourne, 1996

The Hicks Family Collection, Melbourne

Sir John Sulman Competition, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1944, cat. 9

Australian Art: Colonial to Contemporary 1780s - 1990s, August 1996, cat. 67, (illus.)

Paintings about the cinema are not common, although they have attracted many an artist of stature as seen in works such as Herbert Badham's The Cinema, 1958, and Jeffrey Smart's Drive-In Cinema, 2004. Badham used the subject to explore his idiosyncratic use of perspective. Enigmatic is the best word to describe Smart's painting, although he does refer to the one-time phenomenon of the drive-in theatre and the super-sized imagery that is part of cinematography. Weaver Hawkins's Technicolour, c.1944, works in an entirely different vein, providing a fascinating social document of its time. Once, the cinema, or the ‘pictures’ as they were commonly called, were the centre of public entertainment, to be displaced later by television. Today, we tend to forget that colour movies were once very special, enough to draw large crowds in their own right. Hawkins draws our attention to this in titling his painting after the wondrous invention of ‘technicolour’. He also presents other social phenomena, which have now passed into the shades of history. In the 1940s the whole family went to the pictures to take their pleasure together, as seen to the left foreground of his painting. Families often had weekly reserved seats, especially for Friday and Saturday nights. They were grand occasions, a touch of which is reflected in the spacious interior, noble proscenium arch and gold-edged red velvet curtains. People dressed formally, both men and women wearing hats, as depicted by Hawkins. There were likewise pretty, uniformed usherettes to show you to your seats after lights went dark. In the first part of the forties the pictures were also a great form of escapism from the hard times of the Second World War. Make-believe was there on the screen for all to enjoy, captured by Hawkins in the ever-beautiful and ever-youthful film stars.

As an engaging scene of contemporary life, Hawkins entered Technicolour in the Art Gallery of New South Wales's 1944 Sulman Prize- awarded to ‘the best subject painting or genre painting’. The prize went to Jean Bellette's Iphigenia in Tauris, of a lady long dead. Hawkins had been horrendously injured in the World War I battle of the Somme. His miraculous survival and the subsequent development of his art was a triumph of the human spirit. Technicolour is a fine example of his family pictures, which centred on domestic tranquillity, much aided by their striking directness. As Daniel Thomas once observed, Hawkins ‘…dwelt in an oasis of happiness. His early glimpse of doomsday ensured a determination to make the most of the day-to-day.’1

1. Thomas, D.R., ‘Foreword Note’, Weaver Hawkins 1893 - 1977: Memorial Retrospective Exhibition 1977 - 1979, Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, 1977, no pagination

DAVID THOMAS