INDOOR STILL LIFE, 1913

MARGARET PRESTON

oil on canvas

53.5 x 65.5 cm

signed twice lower right: M. R. Macpherson / M. R. Preston

Mrs John S. Teulon, Melbourne

Mrs Lambert Latham, Victoria

Joshua McClelland Print Room, Melbourne

Ken and Joan Plomley Collection of Modernist Art, Melbourne, acquired from the above in July 1978

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts Salon, Grand Palais, Paris, 13 April – 30 June 1914, cat. 811 (as ‘La Cuisine (Nature Morte)’)

New English Art Club (Winter), RBA Suffolk Street Gallery (Galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists), London, December 1914, cat. 114 (as ‘The Kitchen’)

Forty-Fifth Autumn Exhibition of Modern Art, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England, 9 October 1915 – 8 January 1916, cat.1002A (as ‘The Kitchen’)

Society of Women Artists, Sixty-Second Annual Exhibition, Galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists, London, 4 February 1917, cat. 198 (as ‘Indoor Still Life’)

Exhibition of Paintings etc. by Misses Margaret R MacPherson and Gladys Reynell, Preece’s Gallery of Australian Art, Adelaide, 15 – 30 September 1919, cat. 1 (as ‘The Kitchen’)

Royal Art Society of NSW, Forty-First Annual Exhibition, Exhibition Gallery, Department of Public Instruction, Sydney, 9 August 1920, cat. 3 (as ‘Indoor Still Life’, label attached verso)

Early Australian paintings and prints, Joshua McClelland Print Room, Melbourne, December 1978 (as ‘Summer morning, still life’, c.1916’)

Margaret Preston, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 29 July – 23 October 2005 and touring in 2006 to, Ian Potter Centre, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide (as ‘Still Life: Sunshine Indoors’, 1914)

Express and Daily Telegraph, Adelaide, 10 January 1914, p. 12

Fry, E., ‘Australian Artists in Paris’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 1 July 1914, p. 5 (as ‘The Kitchen’)

‘New English Art Club’, Morning Post, London, 2 December 1914, p. 3

‘New English Art Club’, Standard, London, 2 December 1914, p. 2 (as ‘The Kitchen’)

Rutter, F., ‘Society of Women Artists’, Sunday Times, London, 11 February 1917, p. 5 (as ‘Indoor Still Life’)

‘Society of Women Artists’, Morning Post, London, 15 February 1917, p. 4

Art and Australia, Fine Arts Press, Sydney, vol. 16, no. 2, Summer December 1978, p. 105 (illus., as ‘Summer morning, still life, c. 1916’)

Edwards, D., Peel, R. and Mimmocchi, D., Margaret Preston, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2005, pp. 37 (illus.), 282 (as ‘Still Life: Sunshine Indoors’, 1914)

Margaret Preston Catalogue Raisonné of paintings, monotypes and ceramics, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2005, CD-ROM compiled by Mimmocchi, D., with Edwards, D., and Peel, R. (as ‘Still Life: Sunshine Indoors’, 1914)

On 8 February 1912 Margaret Rose Macpherson sailed for Europe on a second study tour. Her sights were set on Paris, where she hoped to pick up ideas about design and colour. Her preferred field was still life — a genre where an artist might create her subject and not be its servant. Convinced both that 'art is personal and of the spirit'1 and that an emotive subject was not a pre-requisite, she saw her tools of expression as colour and drawing. In Paris she joined like-minded artists, Bessie Davidson, Rupert Bunny and his circle (of whom Georges Oberteuffer and Richard Miller later claimed to have taught her) and countless others, including those responsible for the exciting Rhythm magazine, in analysing Japanese art, Post Impressionist paintings, and the ways by which practitioners in the arts of music and dancing evoked mood, spirit and bodiliness.

Eighteen months later Macpherson summarised what had impressed her in Paris.2 One painting had stirred her deepest feelings, Gauguin's Ia Orana Maria, 1891. Gauguin's methods were incalculable, however, so she looked to another Post Impressionist whose work attracted her. Although Edmond-François Aman-Jean’s palette lacked Gauguin's inspired boldness and his symbolism, ‘a little sad but full of feeling,’ as well as his daring intuition, he had the advantage of having been a fellow student and for a few years shared a studio, with Georges Seurat, and believed, with him, that 'a sense of order is the basis of all art'.3 Systematised colour and design, rife in Paris, was a springboard for the personal expression Margaret Macpherson was looking for. There was an added advantage too, in that Aman-Jean was now a prominent leader and power-broker in exhibiting circles in Paris. He was on the judging panel for the Société National des Beaux-Arts (or New Salon) where, in April 1913, Macpherson had her first painting accepted for exhibition

Preston.jpg

WITH LITTLE JIM, c.1915, courtesy of Art

Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Macpherson, and one of her ex-students from Australia, Gladys Reynell, worked for four summer months (June – September 1913) on the Île de Noirmoutier, off Brittany. Indoor Still Life, 1913 was painted looking into the garden of the house where they were staying, with Macpherson harnessing her newly found skill to a vision of warm and cool colours that was both unusual and satisfyingly – even brilliantly – natural. She employed Aman-Jean's delicate palette of greens, pale yellows, pinks, blues, white and black, but where the French painter intermingled warm with cool hues, Macpherson divided the colours into two groups and applied them in separate zones, thereby giving the concept of divided colour a fresh significance. The colour of light differs from one corner of the canvas to the other. In the upper-right, the sun beats down upon the garden, perfuming the pink roses and relaxing and fattening the textures of green leaves and sandy soil. (Earth and foliage is similarly sunlit and slack in The Windmill, a small landscape dating from that summer.) In the lower segment, reflected light sparkles coolly in shadow, bouncing with restless mobility from surface to surface of glazed white porcelain, glassware, metal knives and forks. Indoor Still Life attests to the sensuous truth in the theory, so memorably stated by Seurat, that gaiety is expressed by luminous hues and lines rising upwards, and calm is expressed through an even balance of light-and-dark and warm-and-cool colours, and by lines in a horizontal direction.

Margaret Macpherson – soon to be Margaret Preston – was not a prolific painter. Most if not all her major paintings, of which this is one, involved time and many sketches, as the artist sought, fought for and eventually found a composition and colour scheme that expressed a resonantly individual idea. Stylistically, Indoor Still Life stands near the beginning of a key group dating between 1912 and 1917. On the cusp of two periods in the artist's career, it is both a tour de force in the painting of reflected light (her previous interest) and introduces a rhythmic, sculpturally-informed composition and colours keyed like music. Another still life from Île de Noirmoutier, Holiday Still Life 1913, with richer colour and less interest in reflected light, represents a further step into the new style.

Macpherson and Reynell left France for London at the end of the summer. Visiting Macpherson a couple of months later an Australian columnist was shown a painting (not one of two paintings currently on exhibition) which seems to be the work now known as Indoor Still Life:4

I saw one picture of Miss Macpherson's of an out-of-doors breakfast table, every inch of it painted with the extraordinary technical skill that has made her work notable in Australia. The whole is bathed in soft sunlight, and beyond there is a little garden path winding away between green garden beds, that gives a delightful air of romance. In all the pictures there is a rare originality of conception and breadth of treatment.5

The column, dated 5 December, focused on how London was responding to Macpherson's paintings:

Miss Margaret R. Macpherson ... has begun her career in London triumphantly, by having two of her brilliant still life pictures accepted and hung at the "New English Art Club's" exhibition. This is one of the shows where you can only exhibit by invitation, and even then your work may not be accepted ... In this case the secretary simply swooped down on Miss Macpherson, carried off the pictures, and the deed was done. The critics greeted her appearance in the most flattering way, and she has had remarkably fine notices from all sides. This clever Adelaide girl's latest work has a fascinating and very modern note in it to add to her always remarkable technique, and her first London success is pretty certain to be followed by many more. In fact, one noted artist here tells me that there are few people to touch her in her particular line.6

Macpherson's London reputation grew from year to year between 1913 and 1917 (by which time her war work had swallowed most of the hours previously given to painting). Reports of her success relayed by the Australian press did not encompass the contexts in which she was praised. Art criticism was unapologetically misogynist at that time of suffragette action in the UK and wartime hysteria also weighed heavily against women. Of those who wrote about Macpherson's paintings, Frank Rutter dissented from the general tone of heavy-handed masculine pomposity and clubbishness. Others, including Sir Claude Phillips, praised her work but did not disguise their belief that women by virtue of their gender were incapable of creative art. The following obscurely phrased preamble from the Athenaeum's anonymous critic is typical:

On not a few occasions in recent years we have recognised in women artists considerable capacity in the painting of still-life — a department of art in which there is, indeed, considerable scope for originality and initiative, but in the practice of which an attitude of mind or code of principles can, when once assimilated, be applied with tolerable precision. This makes it an excellent field for exercises under – or after — a master, and the works to which we have referred usually look as if they might have been produced under those conditions. While they thus cannot be adduced to confound the profane who would deny women's possession of creative power in the arts, they are none the less useful in providing the wide range of concrete examples by which alone, perhaps, an existing method may penetrate to the remote corners where predestined genius catches the hint of a further development. Miss Margaret Macpherson's ... are examples of such "school-pieces." Bringing nothing new into art, they may nevertheless disseminate certain sound principles of painting not yet (as is evident enough in other parts of the exhibition) common property in all circles. Based apparently on the work of, say, Mr Peploe and Mr William Nicholson, they seem to us the best things on the walls. (Athenaeum, 20 February 1915, 172)

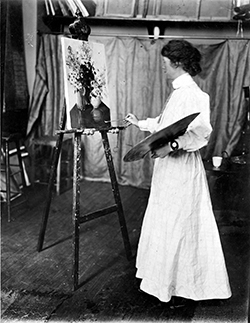

MARGARET PRESTON PRINTMAKER (1) - Supplementary Image.jpg

STUDIO, c.1909

Australia, Adelaide

Her supposed inferiority as a woman incapable of creative effort affected Macpherson only to the extent that she set herself, and art history, some unnecessary hurdles to jump over. Marrying soon after the war, in mid-career, having made a 'name' for herself in the art circles of London and Australia, she chose to switch her professional name to Preston, as if to start again. Exasperatingly, she showed a similar lack of concern for maintaining the title of a painting from exhibition to exhibition. For that reason it has proved difficult if not impossible to establish the original title and subsequent exhibiting history of many of Macpherson's pre-1920 paintings — including this work. To illustrate the difficulty, the painting she showed in the New Salon in 1913 as Novembre sur le balcon (nature morte), had another name, Still life: December Sun, at the New English Art Club (NEAC) in December 1913 and in Adelaide in 1919 was December Sunlight, Paris. The problem of title-shift is complicated by the artist using the same title for more than one work (The Window shown in 1914 is different from a work of the same title shown in 1916, for example). This is compounded by the generic nature of the artist's subjects – flowers, fruit, crockery, tables, windows, indoor light, outdoor light – and ambiguities of representation. More often than not, her still lifes do not stage a situation that could be enacted in real life. There will be knives and forks but no plates, coffee pots but no cups, a water jug but the adjacent glass will be filled with flowers. Ditto with the setting: the table in Indoor Still Life may be indoors against an open window (if so, the pane lies flat against the outside wall like a shutter); equally, it could be outdoors in the corner of a terrace and separated from the garden by a low wall. Macpherson chose and composed her objects, setting, light effects for their formal values.

Accordingly, her idea of a picture was not always what a superficial view would identify as the subject. Some of the more obscure titles identify an aspect of a work that only the artist, or like-minded viewers, would regard as significant. The Window, 1916, an opulent work that was much praised when it appeared in the Royal Academy in 1916, now carries the title Anemones in response to its clamorous flowers, bright-coloured and intensely-patterned; the window of the original title barely shows at the top of the picture, where the edge of a curtain, striped white, black, blue and violet, states the colour-key and the top-and-bottom notes for the work as a whole.

The title Indoor Still Life (a firm title, since it is written on an exhibition label pasted to the back of this canvas) dates from 1920, when a reviewer mentioned that the work had been shown at the New Salon.7 Macpherson showed only two paintings at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts Salon (SNBA): the first is ruled out by its contents, which leaves us with the prosaically named ‘La cuisine (nature morte)’ [Kitchen still life], shown at the SNBA in April 1914,8 when the excellent journalist Edith Fry reported from Paris:

Miss Macpherson ... has sent to the National one of her still-life studies, which she calls ‘The Kitchen’. Miss Macpherson is unequalled as a painter of white, and her execution of white china on a light tablecloth shows consummate art.9

1. Preston, M., 'Meccano as an ideal', Manuscripts (Geelong) No 2, June 1932, p. 91

2. Margaret Macpherson letter to Norman Carter from the Ile de Noirmoutier, 18 August 1913 (Norman Carter papers, ML MS 471/1)

3. Aman Jean letter to Gustave Coquiot, 2 August 1923, published in Herbert, R. L., Georges Seurat 1859-1891, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 1991, Appendix B, pp. 377 – 78

4. In favour of Indoor Still Life being the work described in a ‘letter from London’ dated 5 December 1913, it is the only work in Macpherson's known output from the years 1912 – 1918 to have a ‘a path winding away between green garden beds’ that might be said to impart ‘a delightful air of romance’ (Holiday Still Life 1913 has a garden path that is straight and ends swiftly and unromantically at a fence). Additionally, this is the only painting from 1913 – 18 with scintillating light effects on glass, metal and porcelain – that being 'the extraordinary technical skill that ha[d] made her work notable in Australia’.

5. Exile, 'Woman's Letter from London', 5 December 1913, Chronicle, Adelaide, 10 January 1914, pp. 56 – 57

6. ibid.

7.’Mrs Preston's Paintings’, Sunday News, Sydney, 15 August 1920 [http://pressclippings.ag.nsw.gov.au/libItemDetail.asp?searchWords=mrs+pr...

8. Between first exhibition and 1920, The Kitchen appeared at the NEAC in December 1914, at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool in October 1915, at the Society of Women Artists in February 1917 (as Indoor Still Life, 20 gns'), and as The Kitchen, 20 gns' in Macpherson's joint exhibition with Reynell in Adelaide in September 1919 where a catalogue note stated that it had been shown at the NEAC and SNBA.

9. Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 1 July 1914, p. 5

MARY EAGLE